Credit: Save the Children / Sam Tarling

Gaps in education attainment and achievement are the result not only of the general social and economic context but also of its reflection in education systems: Policies, processes and resource allocation. In other words, gender equality in education system outputs and outcomes depends, to some extent, on gender equality in the choice of inputs. Regulations, general and school-specific policies, curricula, and teacher education must be designed through a gender lens if they are to contribute to equality. A few examples in this section highlight selected connections.

PREGNANT GIRLS SHOULD NOT BE EXCLUDED FROM SCHOOL

Girls’ early school leaving often comes just before or after early marriage or in the wake of pregnancy. About 90% of births among 15- to 19-year-olds occur within marriages or unions. Globally, nearly 16 million girls aged 15 to 19 give birth each year; 2 million of them are under 15 (UNFPA, 2015b). In Chad, Mali and Niger, child marriage and early pregnancy rates exceed 160 per 1,000 15- to 19-year-olds. Pregnancy has been identified as a key driver of dropout and exclusion among female secondary school students. Longitudinal data from Madagascar confirm that teenage pregnancy leads to early school leaving (Herrera Almanza and Sahn, 2018).

Throughout sub-Saharan Africa, some steps have been taken to protect pregnant girls’ right to education. A recent report by the NGO Human Rights Watch identified 18 countries with no laws, policies or strategies supporting girls’ right to go back to school after pregnancy. Equatorial Guinea, Sierra Leone, the United Republic of Tanzania and Togo enforce a total ban on pregnant girls and young mothers in public schools.

However, 25 countries were found to have introduced some measure to enable girls to continue their education. Of those, four, including Cabo Verde and Gabon, have policies or strategies allowing pregnant girls to stay in school, without prescribing a mandatory absence after birth. Six countries, including Benin and Lesotho, have laws affirming pregnant girls’ right to stay in school, but lack policies on how to enforce that right. Thus, in the absence of guidance, schools may still expel pregnant girls. And in 15 countries, policies allow pregnant girls to return to school as long as they fulfil certain conditions. In Botswana, the Kingdom of Eswatini and Zambia, girls are excluded from school for between 6 and 18 months after giving birth. They are often not allowed to return to the same school (Human Rights Watch, 2018).

Early pregnancy is an important factor in adolescent girls’ early school leaving in Latin America as well. In the Plurinational State of Bolivia, 19% of women aged 15 to 19 who had not completed secondary education cited marriage as the main reason, and 14% cited pregnancy. In Chile, being a mother reduces the likelihood of completing secondary education by between 24% and 37% (Kruger et al., 2009). In Mexico, among 15- to 29-year-old women who dropped out of school in 2013, 8% listed pregnancy or having a child as a reason why they left school early, and 11% cited getting married or entering a union. To address the issue, Mexico’s Ministry of Public Education has committed financial resources to support students at risk, offering scholarships with a gender component to help adolescent mothers stay in school. From 2013 to 2015, it offered more than 700,000 scholarships aimed at keeping girls in school (OECD, 2017).

SCHOOL ENVIRONMENTS ARE OFTEN NOT SAFE OR GENDER-INCLUSIVE

Girls and boys should feel welcome in a safe and secure learning environment. Governments, schools, teachers and students all have a part to play in ensuring that schools are free of violence and discrimination and provide a gender-sensitive education of good quality. To achieve this, governments need to develop non-discriminatory curricula, facilitate teacher education and make sure sanitation facilities are adequate. Schools are responsible for addressing school-related violence and providing comprehensive sexuality education. Teachers should follow professional norms regarding disciplinary practices and provide unbiased instruction. Students must also behave in a non-violent, inclusive way.

School-related gender-based violence affects millions of boys and girls

School-related gender-based violence, in its physical, sexual and psychological forms, affects children and youth around the world in terms of their school attendance, well-being and learning. Unequal gender norms and power relations feed into manifestations of violence in and around schools, often with grave consequences for education attainment and achievement, affecting both boys and girls but in different ways. Schools should serve as models of respectful behaviour, but too often they are sites of physical violence. About 720 million school-aged children live in countries where they are not fully protected by law from corporal punishment in school (UNICEF, 2018a). Even where legal provisions ban such practices, the law is often not fully implemented. In India, at least 65% of children are physically punished by teachers, despite corporal punishment being banned in schools. Research in Gurugram, Haryana state, found that gender-specific forms of punishment were used against disadvantaged children. Girls experienced sexist verbal abuse about their age, weight, appearance and marriage prospects. Boys were more likely than girls to receive physical punishment in later primary grades. Most teachers used corporal punishment routinely and most parents approved, often punishing children at home upon finding out that teachers had beaten them (Agrasar, 2018).

Sexual violence is strongly related to unequal distribution of power between men and women. Its prevalence often increases in contexts of conflict and displacement (Box 9). But is a particularly difficult form of violence to monitor and report. In Kenya, sexual violence is believed to affect about one-third of girls and one-sixth of boys under 18, but most do not discuss their experience or receive help (Population Council, 2018). Among Kenyan 13- to 17-year-olds who experienced at least one episode of sexual violence in the previous 12 months, boys most often reported that it occurred at school, while girls reported that it occurred on the way to school. For most respondents who experienced unwanted sexual touching prior to age 18, school was the setting of the first incident (UNICEF/CDC/Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, 2012).

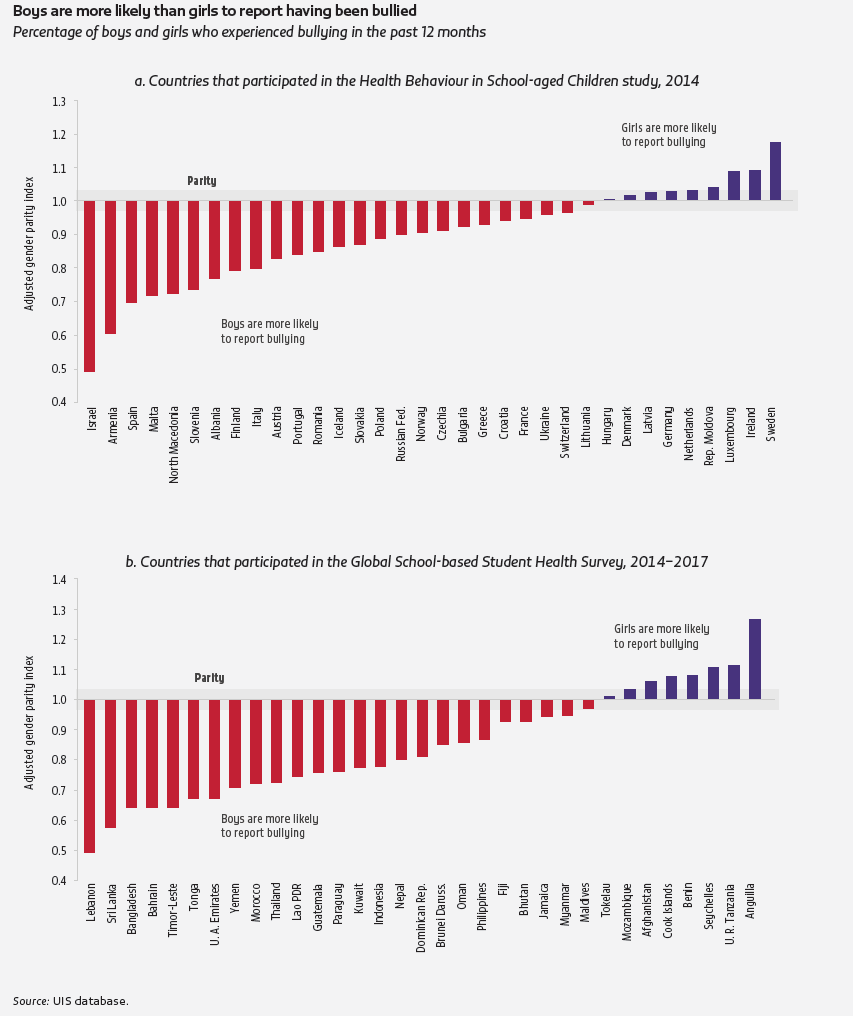

Psychological violence is also widespread. Bullying is intentional, aggressive and repeatedly occurring behaviour in the context of a real or perceived power imbalance. It affects millions of children and youth around the world. It occurs in schools and, increasingly, online. In international surveys by the World Health Organization (WHO), one in four adolescent students in mostly high-income countries (the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children study) and one in three in mostly low- and middle-income countries (the Global School-based Student Health Survey) reported having been bullied in the previous 12 months. In countries including Lithuania, Myanmar, Nepal and the Philippines, the prevalence rate was 50% or more. In most countries, boys are more likely than girls to report bullying (Figure 13).

As most data sources observe student performance and the incidence of bullying simultaneously, it is difficult to establish cause and effect. However, some recent analyses have argued that bullying does lead to lower student learning. In Recife, Brazil, grade 6 students who had been bullied achieved significantly lower scores in mathematics (Oliveira et al., 2018). In Ghana, where bullied grade 8 students also suffered lower achievement scores in mathematics, the effects were stronger for female students but mitigated when the teacher was a woman (Kibriya et al., 2017).

All forms of school-related gender-based violence require comprehensive, coordinated responses, including appropriate regulations, policy and leadership initiatives, reporting mechanisms, community and student partnerships, evaluation of incidents, and staff or teacher involvement (UNESCO, 2017). Education programmes that help students to communicate, understand interpersonal differences, reject gender norms and learn other life skills can help them address bullying, as both victims and perpetrators. In the United States, the Second Step programme had reached more than 8 million students in over 32,000 schools by 2016. It taught communication and decision-making skills to help students navigate pitfalls such as peer pressure, substance abuse and bullying. At the end of the programme, students in Illinois intervention schools were 56% less likely to report homophobic name-calling than those in schools where the programme was not administered (UNESCO/UN Women, 2016).

Figure 13

An education of good quality for boys and girls must include comprehensive sexuality education

Comprehensive sexuality education is a curriculum-based process of teaching and learning about the cognitive, emotional, physical and social aspects of sexuality, going beyond the narrower approaches that were more common in the past. It improves sexual and reproductive health-related outcomes, such as HIV infection and adolescent pregnancy rates, which in turn helps expand education opportunities. It disrupts harmful gender norms and promotes gender equality, which helps reduce or prevent gender-based violence and hence create safe and inclusive learning environments. And it is a key component of a good-quality education: As an active teaching and learning approach centred on students, it helps develop skills such as critical thinking, communication and decision-making, which empower students to take responsibility for and control their actions and help them become healthy, responsible, productive citizens.

The importance of comprehensive sexuality education is recognized in the SDG monitoring framework. As part of SDG 5, global indicator 5.6.2 refers to ‘Number of countries with laws and regulations that guarantee full and equal access to women and men aged 15 years and older to sexual and reproductive health care, information and education’. As part of methodological work developed by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), with support from WHO and UN Women, six pilot countries were asked to indicate whether their national curricula or guidelines on sexuality education covered eight topics: Relationships; values, rights, culture and sexuality; understanding gender; violence and staying safe; skills for health and well-being; human body and development; sexuality and sexual behaviour; and sexual and reproductive health. All eight topics were covered in Albania, Sweden and Zambia. Mexico covered half the topics, Sri Lanka two and Tunisia none.

Comprehensive sexuality education leads to more responsible and healthier sexual behaviour. In the United States, students aged 12 to 17 who were given comprehensive sexuality education were taught about the menstrual cycle, the right to say ‘no’ to sex, birth control methods, abstinence as a way to prevent sexually transmitted diseases, sexuality as a natural part of life, and signs and symptoms of sexually transmitted diseases. Youth exposed to these topics were twice as likely to use condoms as those who were not (Green et al., 2017).

Comprehensive sexuality education is also an important factor in teenage pregnancy prevention. In India, the Development Initiative Supporting Healthy Adolescents worked to help prevent child marriage and adolescent pregnancy by scaling up health services and providing comprehensive sexuality education, combined with mentoring, community support and life skills training. As a result, the average age of marriage increased from 15.9 to 17.9 years and contraceptive use increased by nearly 60% among married adolescents (UNFPA, 2015a).

Too many schools lack sanitation facilities

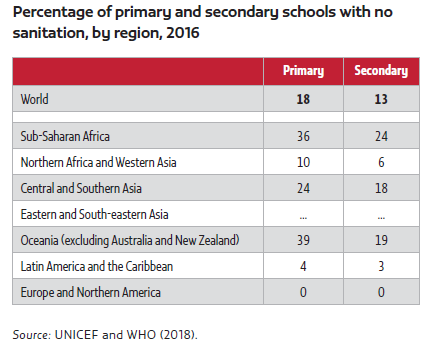

Water and sanitation facilities, especially singlesex toilets and menstrual hygiene management facilities, need to be available to girls in school to ensure a dignified, gender-equitable learning environment, reduce absenteeism and facilitate girls’ retention in adolescence (UNESCO, 2018a). In 2018, the WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene provided a first global baseline report on the school sanitation situation. In 2016, it found, 18% of primary schools and 13% of secondary schools around the world had no sanitation facilities. The percentage of secondary schools without facilities was 24% in sub-Saharan Africa, 19% in Oceania (excluding Australia and New Zealand) and 18% in Central and Southern Asia (Table 1).

Table 1

Many countries have developed national guidelines for menstrual hygiene management in recent years. However, in 2016, only 53% of schools globally had access to handwashing facilities with soap and water, which implies that around 335 million girls went to primary and secondary schools that lacked these essential ingredients of menstrual hygiene management. A state-level analysis across India in 2017 found that 62% of schools had dustbins for disposal of menstrual hygiene materials and 64% provided menstrual hygiene education. Moreover, variation in sanitation access by region is wide, often to the disadvantage of rural schools. In Nicaragua, 64% of urban schools but 32% of rural schools had improved basic sanitation services (UNICEF and WHO, 2018).

Such data rely on aggregated and indirect sources, which may be neither complete nor fully validated. On-site surveys often demonstrate that the situation is in fact worse. Direct observation of access, continuity, quality, quantity and reliability indicators of water, sanitation and hygiene facilities in a random sample of 2,270 rural schools in six sub-Saharan African countries showed that just 1% of those in Ethiopia and Mozambique had improved water sources on premises, improved sanitation, and water and soap for handwashing. Less than 20% of rural schools across the six countries had at least four of five recommended menstrual hygiene services (separate-sex latrines with doors and locks, water for handwashing, waste bin) (Morgan et al., 2017).

TEACHING IS FREQUENTLY A FEMALE PROFESSION WITH MEN IN CHARGE

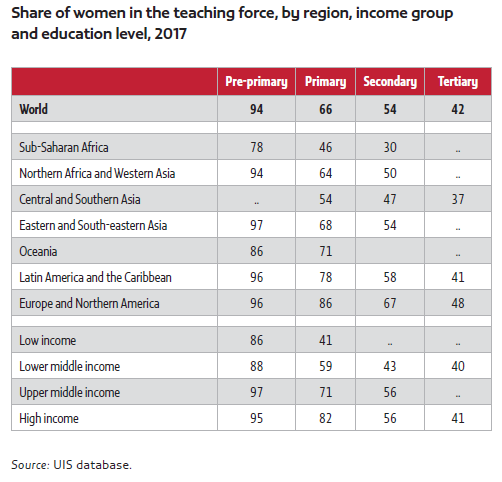

Teaching has been characterized as a ‘female’ profession, especially at lower levels of education (Mitchell and Yang, 2012). Very few men work in early childhood education, at least partly because of persistent gender stereotypes and norms. There are far more men at higher levels of education and in school leadership positions. Nearly 94% of teachers in pre-primary education, but only about half those in upper secondary education, are female. Disparity between male and female teachers exists not only across education levels, but also across regions. The proportion of women among primary school teachers in low-income countries (41%) is half that in high-income countries (82%) as a result of multiple factors, including the legacy of gender disparity in access to education and norms that prevent employment of women as teachers (Table 2).

Table 2

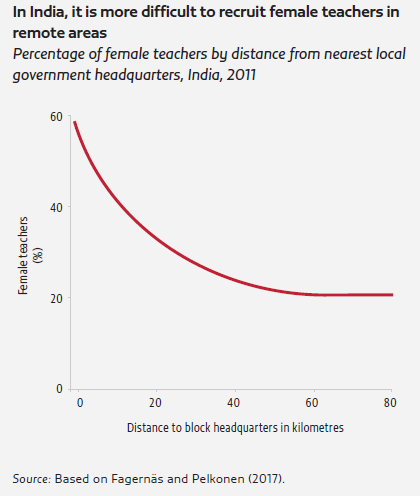

Many countries struggle to deploy female teachers where they are most needed In rural areas, attracting and retaining teachers, particularly female teachers, is often a challenge. In India, the share of female teachers declines with the remoteness of schools, from 60% when the school is located at the local government seat to 30% when it is 30 km away (Fagernäs and Pelkonen, 2017) (Figure 14).

In Liberia, cases of sexual harassment were reported in training institutes in rural areas. Finding suitable accommodation for teachers in rural areas was reported to be hard, especially for female teachers, who have additional needs for safe housing (Stromquist et al., 2013). Similar challenges were reported in Togo, Uganda and the United Republic of Tanzania (Stromquist et al., 2017). In Mexico, an unwritten rule against assigning female teachers to work in rural areas has been gradually relaxed due to changing work conditions and a general shortage of teaching jobs, which has led to a more balanced gender ratio (Luschei and Chudgar, 2017).

Figure 14

More equitable teacher deployment matters for education outcomes in contexts with wide disparity at girls’ expense. In rural Pakistan, recruiting local and female teachers had positive effects on girls’ learning, reducing gender disparity in academic achievement (De Talancé, 2017). The lack of such teachers is a particular problem in conflict and displacement settings (Box 10).

While research evidence is scarce, a natural experiment in West Bengal state, India, assessed the effect of randomly assigning village councils to be headed by a woman on the aspirations of adolescents and their parents. In villages that were assigned a female head over two election cycles, the gender gap in occupational and other aspirations closed by 25% in parents and 32% in adolescents, compared with villages with a male head. The gender gap in educational attainment aspirations was eliminated among adolescents (Beaman et al., 2012).

Gender norms often account for persistent disparity in education leadership

Evidence suggests that gender disparity patterns differ between education leadership positions and teaching positions, although data are not as systematically available for the former as for the latter. An analysis drawing on 35 mostly high-income countries, most of which had participated in the OECD’s 2013 Teaching and Learning International Survey, indicated that the share of female head teachers in lower secondary schools was 18 percentage points lower than the share of teachers, on average. The difference was greater than 30 percentage points in countries including Finland, Japan and Portugal, and largest in the Republic of Korea, where the share of female teachers was 68%, compared with 13% for head teachers (UNESCO, 2018).

Japan stood out as the high-income country with the most persistent challenges in improving gender equality in education leadership: 39% of teachers overall, but only 6% of head teachers, are female. National policies such as the 1985 Gender Equality in Employment Act and the 1999 Basic Law for a Gender-Equal Society were meant to facilitate improvement in female employment, and the Cabinet Office’s Gender Equality Bureau is responsible for pursuing gender equality. The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology runs gender parity programmes within a policy framework set by the Cabinet. The ministry has initiated a variety of national interventions to bridge the gender gap, including in teaching and school leadership; these include improving child care support, providing recurrent education support for re-employment, improving scholarly support for women researchers and improving educational support for human capital development. However, progress has been slow, as the latest administrative data at the prefecture level show. Between 2013 and 2017, the share of female school principals increased by only half a percentage point and remained below 7%. The share increased by five percentage points in three prefectures, including Hiroshima (from 6% to 11%), but declined in several, including Akita (from 8% to 4%). The share of female vice-principals showed more improvement, rising by two percentage points to just over 10%; the share ranged from 3% in Yamanashi to 22% in Okinawa, where it almost doubled. Male teachers were still 7 times as likely as female teachers to be promoted to a head teacher position in primary education in 2017, and 11 times as likely in lower secondary education (Yurita et al., 2019).

Teachers need to be trained to challenge gender discrimination

Teacher education is critical in preparing teachers to create a safe and inclusive classroom and school environment and to teach students how to act responsibly in school and out. Training materials should help teachers explore how gender discrimination and norms can be challenged. Gender-sensitive approaches can be incorporated at key stages of teacher education when classroom management and discipline approaches are introduced, in both pre- and in-service courses.

There are few internationally comparable data on teacher participation in gender-sensitive training. Scattered national-level information shows that exposure to such training is relatively uncommon. In Italy, teacher education rarely addresses gender equality issues; teachers are not systematically trained and thus lack relevant competence. Teacher training and school initiatives on gender equality are mainly based on individual interests and commitments. In Romania, evidence indicates that teachers are not prepared to address gender equality, and textbook content and school processes reinforce gender stereotypes (Juhasz and Pap, 2018).

In Uganda, the 2016 Gender in Education sector policy is committed to developing and implementing a genderresponsive education and training curriculum for teacher educators and to promoting gender-responsive teaching and learning materials for schools and colleges. In addition, the 2015-2019 National Strategy for Girls’ Education committed to scaling up gender training for secondary school teachers and introducing gender training as a comprehensive and integral part of the teacher training curriculum and performance review. However, a survey of 70 secondary school teachers found that about 45% had never received gender-sensitive pedagogy training. Among those who had, 43% reported that the training lasted a week or less, and little was known about the quality of training in general. As a result, many teachers still judged girls based on stereotypes, seeing them as shy and with low self-esteem (Nabbuye, 2018). Such obstacles are multiplied in contexts of migration and displacement (Box 11).