Target 4.6: Literacy and numeracy

By 2030, ensure that all youth and a substantial proportion of adults, both men and women, achieve literacy and numeracy

CREDIT: Stefanie J. Steindl/UNHCR. Smiles of understanding from Mohammed Abdullah from Iraq (left) and Gholem Reza Ramazani from Afghanistan (right) as they learn media skills in Austria.

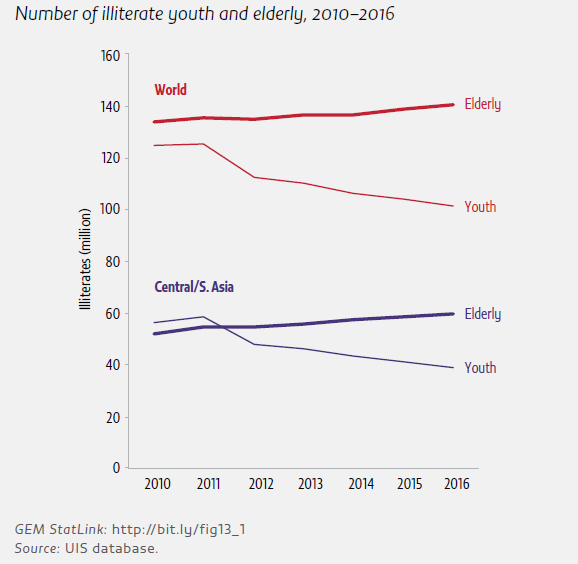

The world literacy rate reached 86% in 2017, although it remains as low as 65% in sub-Saharan Africa. Progress in youth literacy — and shrinkage of the youth cohort — has been rapid enough in recent years to lead to an absolute decline in the overall number of illiterate youth aged 15 to 24, largely driven by Asia. But the number of illiterate elderly, aged 65 and above, continues to grow; there are now almost 40% more illiterate elderly than illiterate youth (Figure 12).

Figure 12: There are almost 40% more illiterate elderly than illiterate youth

Isolated illiterate individuals, who live in households where no member can read, tend to have worse labour market and quality of life outcomes than proximate illiterates, who live with one or more literate household members.

Isolated illiteracy tends to be higher among rural dwellers. In richer countries, isolated illiterates are relatively older than proximate illiterates, whereas the converse is true in poorer countries. One explanation is that most illiterates in poorer countries live in multigenerational households and hence are more likely to live alongside younger, more educated family members.

Accordingly, literacy interventions should be targeted at old adults living in one- or two-person households in richer countries and at socio-economically marginalized young adults, often living in rural areas, in poorer countries.

Previous year’s Target 4.6