Countries with large gender gaps in education need to make their education sector plans more responsive

2019 Gender Report

CREDIT: Nour Wahid/Save the Children

Designing and scaling up a good programme on gender equality in education is a shared responsibility. Donors need to carry out due diligence and collect relevant information to prove interventions’ sustainability. Governments need to be receptive to good ideas that are rooted in national education realities, and take all measures necessary to adopt and roll them out. The first step is to incorporate the ideas in national education plans, as one sign of a commitment to applying a gender lens in the education policy and planning cycle (UNESCO, 2018a).

The GEM Report team sought to determine whether governments consider donor intervention effectiveness in relation to gender equality in education and, if so, whether they take note of the most successful interventions to include them in their education sector plans. Education sector plans should express how governments mean to tackle key challenges to achieve key objectives. While plans are not expected to list detailed actions, they should indicate what programmes will be the main vehicles for achieving their objectives and how much the programmes will cost. If gender-unequal norms, institutions, policies, environments and resource allocation rules form a major constraint for achievement of national education objectives, then a plan should make clear how these bottlenecks are to be addressed.

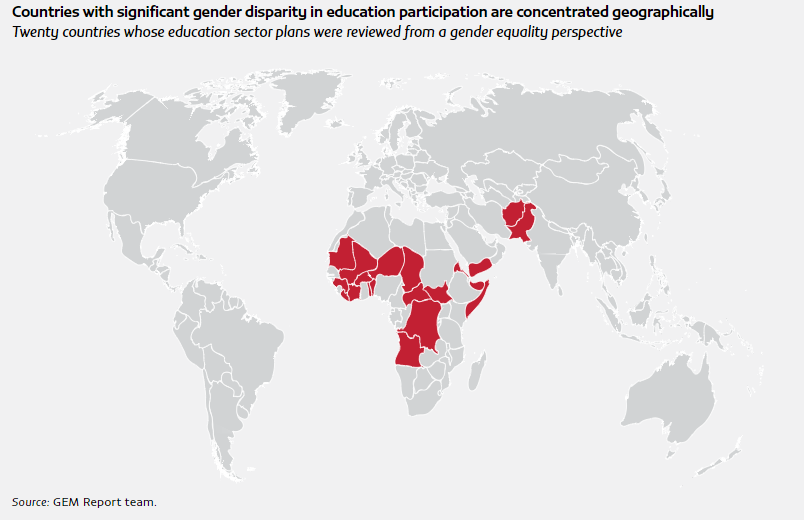

Informed by the variety of interventions initiated and funded by donors to tackle gender inequality in education, the GEM Report team selected 20 countries with some of the highest levels of disparity in education participation to assess whether their education sector plans recognized these priorities and included clear indications of their commitment to respond to these needs. The analysis included the education sector plans of 17 countries plus the national education plan and 4 provincial education plans of a federal country (Pakistan), the national education strategy of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the national development plan – that is, a plan not specific to the education sector – of Angola.

The countries are situated in five loose and somewhat contiguous geographical groups: Sahel, littoral western Africa, central Africa, in and around the Horn of Africa, and southern Asia (Figure 16). They were selected based on their gender parity index of the gross enrolment ratios in primary, lower secondary and upper secondary education, cross-checked with evidence on gender parity in completion rates. Inevitably, the inclusion of some countries over others has been marginal, as data are patchy in some cases. And countries with low disparity in enrolment may still be characterized by highly unequal gender norms and exclusionary practices in education.

Figure 16

The Global Partnership for Education (GPE) and United Nations Girls’ Education Initiative have published guidelines for education planners which include criteria on what constitutes a gender-responsive education sector plan (GPE and UNGEI, 2017). The guidelines include a checklist of 19 questions in 7 areas, focusing on whether the plan is (1) informed by gender analysis, (2) transacted through a participatory and gender-sensitive stakeholder consultation process, (3) reflective of gender strategies and lessons learned and with gender integrated throughout, (4) backed by adequate financial resources, (5) reflected in the operational plan, (6) backed by necessary institutional capacity and (7) strengthened through gender-sensitive monitoring and evaluation.

To the extent possible, this review has attempted to cover these questions, albeit from a macro-level perspective in some cases. It was not possible to assess accurately whether a participatory and gender-sensitive consultation process had been followed, even where the documents provided some information. For instance, Liberia and Togo mention involvement of ministries dealing with gender as well as representatives of women’s groups. Somalia provides the percentage of female participants in the consultation process. But involvement by these stakeholders is no guarantee that their voices were heard and considered. Chad, meanwhile, had an inclusive process, but it is not clear whether it was also gender-sensitive. Other countries, such as South Sudan, did not mention details of a gender-sensitive process in their plans but that does not mean no consultation occurred. To assess the situation more fully, it would have been necessary to contact all participants, which would have been prohibitive not only for cost reasons but also in practical terms, given the long stretch of time over which the plans were drafted, with some dating from 2010.

Assessing whether an education sector plan is backed by adequate financial resources on gender equality is also a challenge. The budget of Mali’s plan, for example, is not detailed enough to enable assessment. In Guinea, activities promoting gender equality are budgeted, but not enough information is available to assess whether the budget is adequate. Such analysis would require information not just on the absolute amounts budgeted but also on unit costs, to assess whether they are realistic and sustainable, and, especially, on actual spending and its distribution. The operational plans were not always included in the education sector plans or annexes. In those cases, the programme plans or result frameworks were checked to ascertain whether activities related to gender equality were included.

Last but not least, the extent to which an education sector plan anticipates and considers interventions related to those initiated by donors does not necessarily demonstrate that national governments have taken ownership of these ideas. A few plans were clearly drafted with external support, raising questions about national ownership.

If education sector plans are to be gender-responsive in practice and not just on paper, they should reflect effective, donor-supported, gender equality-focused programmes and projects. The GEM Report team reviewed whether the plans incorporated actions responding to the 12 priority areas for gender equality in education reviewed in the previous section.