Donors differ in level and type of support to gender equality in education

2019 Gender Report

Credit: UNHCR/Georgina Goodwin

Official development assistance can be a major source of influence orienting country policies towards gender equality in education in countries with unequal norms and wide disparity in attainment and achievement. This section briefly explores the degree of commitment in donor policies and aid disbursements, using official documents and aid project-level data identified through a ‘gender marker’. It then provides an overview of donor projects using information obtained through a questionnaire sent to selected bilateral donors, international organizations and NGOs, which asked them to describe ways in which their programmes were addressing selected key priorities in girls’ education.

AID POLICIES VARY IN THEIR EMPHASIS ON GENDER EQUALITY IN EDUCATION

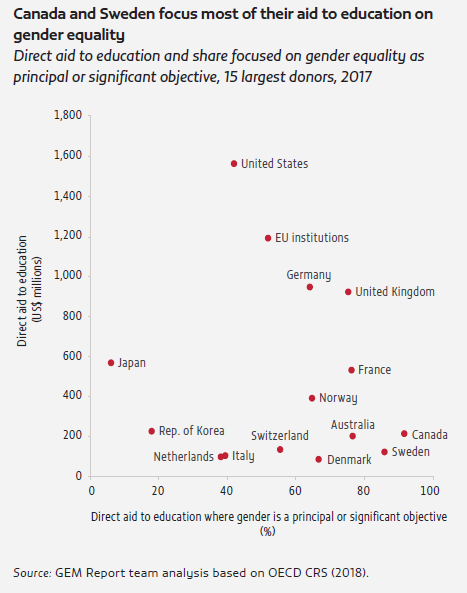

One way to assess the extent to which donors target their projects and programmes on gender equality is through the Creditor Reporting System (CRS) of the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC), which has a filter identifying projects with a focus on gender equality and women’s empowerment. Every disbursement reported to the CRS is marked as: (a) ‘principal’, if gender equality was an explicit objective of the activity and fundamental to its design; (b) ‘significant&’, if gender equality was an important but secondary objective; or (c) ‘not targeted’. Both development and humanitarian aid projects are screened (OECD, 2016). According to this classification, US$4.2 billion, or half, of total direct education aid included gender equality and women’s empowerment as either a significant or a principal objective. Donors allocated nearly 40% of this amount, US$1.6 billion, to primary education. About US$600 million each went to activities related to education policy and management, vocational education and higher education. On average, across DAC member countries, 55% of direct aid to education was deemed gender-targeted, ranging from 6% in Japan to 92% in Canada (Figure 15).

Figure 15

This prioritization broadly reflects the aid policies of the countries involved. Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, for example, has established a Gender Equality Fund as part of its gender equality and women’s empowerment strategy (Australia Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 2019). Canada has proclaimed a feminist international assistance policy (Global Affairs Canada, 2017). Since 2012, the United Kingdom has invested in two rounds of the ambitious Girls’ Education Challenge initiative, which currently operates 27 projects in 15 countries. Two evaluations praised its focus on gender equality, although they questioned projects’ sustainability and the effectiveness of their links to learning outcomes (ICAI, 2016, 2018; Coffey, 2017). By contrast, the United States has not updated its 2012–2016 gender equality and women’s empowerment strategy (USAID, 2012), and the Japan International Cooperation Agency’s thematic guidelines on gender and development have not been revised for a decade (JICA, 2009).

DONORS TACKLE PRIORITIES ON GIRLS’ EDUCATION IN VARIOUS WAYS

For reasons outlined in this report, many countries, usually poorer ones, are still far even from the target of parity in primary and secondary education enrolment, let alone the more aspirational target of non-discrimination in all aspects of the education system. Girls’ education therefore remains a priority area for many actors in international development and is indeed a priority of the French G7 Presidency in 2019. But how do donors approach the main priorities? As part of the preparation for the G7 Ministerial Meeting on Education and Development, the GEM Report team and UNESCO sent a questionnaire to the aid agencies of the G7 countries, selected international organizations and NGOs, asking them to put forward projects for tackling 12 priorities in girls’ education. This section summarizes selected responses by area of priority. It concludes by asking whether donor interventions live up to aid effectiveness criteria and, in particular, whether they have the potential to be scaled up and taken up by governments.

The first three priority areas in the questionnaire were related to gender norms.

1 EMPOWERMENT OF GIRLS AND BOYS TO FIGHT GENDER STEREOTYPES

There is some evidence that mentoring programmes for girls can have positive effects, for example by increasing the likelihood of their remaining and progressing in school, delaying early marriages, and enabling girls to acquire life skills with support from their mentors. The Jielimishe (‘educate yourself’ in Swahili) project is a girls’ club and mentorship programme supported by the UK Girls’ Education Challenge initiative in partnership with SOS Children’s Villages. The project aims to improve the life opportunities of 10,000 marginalized girls in primary and secondary schools in Kenya’s Laikipia, Meru and Mombasa districts by supporting them (by themselves, at home, in school and in their communities) in attending and completing a full cycle of education and transitioning to the next level. The aim is to increase support for girls’ education by communities, school management systems, teachers, school infrastructure and policies. The approach focuses on improving teaching quality through teacher training, coaching and mentorship and encouraging local communities to support girls’ education. The project also supports 7,000 boys.

Sport is increasingly seen as a tool to influence gender norms because it can bring together disadvantaged communities, promoting individual sporting abilities while strengthening skills needed to deal effectively with the demands and challenges of everyday life, such as cooperation, respect, problem-solving, empowerment and communication.

The German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development has supported Africa – Sport for Development (S4D), a regional initiative implemented between 2014 and 2019 in Ethiopia, Kenya, Mozambique, Namibia and Togo, with individual measures carried out on a smaller scale in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ghana, Nigeria and Rwanda. A whole-system approach is reflected in engagement of ministries (e.g. for youth, education, sports or development), community and youth centres, schools and academies, national and international civil society organizations and local sporting institutions. Gender norms are tackled in various ways, including by training female and male coaches, integrating gender-sensitive sports curricula in schools, providing adequate water and sanitation services when sports facilities are built or rehabilitated, and creating safe learning and recreation environments for both girls and boys. Efforts are made to assess the impact on skills development through interviews and focus group discussions.

Across the 9 African countries participating in S4D, more than 57,000 children and young people benefit from the 34 sports grounds created or rehabilitated, and 30% of all coaches trained are female, increasing the involvement of women and girls in sports. In Namibia, the Ministry of Education, Arts and Culture is paving the way for development of a national school sport policy. This ambition is supported by the integration of S4D in grade 10 and 11 curricula and development of a Physical Education for Life teachers’ guide that informs the training of physical education teachers at the University of Namibia.

3 FEMALE PARTICIPATION IN SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY, ENGINEERING AND MATHEMATICS

An important factor in motivating girls to enrol in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) programmes is helping them overcome anxiety and gain confidence in their abilities. To help girls feel confident in making choices, education systems need to improve career guidance and orientation advice services and promote role models.

In South Africa, the UNICEF TechnoGirl programme, in partnership with the Department of Education, has addressed gender inequity in STEM since 2005. Girls aged 15 to 18 from underprivileged urban and rural schools who are doing well academically are placed in corporate mentorship and skills development initiatives to help them gain confidence and link their school lessons to the skills they need to succeed in the labour market. They receive help in making informed career choices, with an emphasis on science, technology and engineering. In addition, over 5,000 young women have received university or college scholarships. There are now TechnoGirl initiatives in all nine provinces, helping build a cadre of future leaders. An evaluation of the project found that only 11% of participants reported they would probably have pursued a different career path had it not been for the project, however, which means there is significant scope for improving targeting.

The Gender-Responsive Quality STEM Education project, funded by Japan, is a partnership between the Francophonie Education and Training Institute, UNESCO, the Centre for Mathematics, Science and Technology Education in Africa, the African Union International Centre for Girls’and Women’s Education, and Microsoft. It targets francophone African countries, including Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Chad, Comoros, Côte d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Djibouti, Madagascar, Mali, Niger and Senegal. The programme provides training lasting 10 days for regional trainers and 5 for national trainers. The training covers enabling and prohibitive factors for girls’ education in STEM, as well as the role of school administrators, heads of teacher training colleges, and representatives from ministerial technical departments in providing leadership to create a school environment conducive to gender-equitable participation in STEM. Participants learn about gendersensitive responsive pedagogy, critically analyse educational resources and are instructed in ways to use ICT to improve girls’ participation in STEM.

5 SECOND-CHANCE PROGRAMMES FOR GIRLS WHO HAVE LEFT SCHOOL OR ARE AT RISK OF LEAVING

Early pregnancy and poverty are among several factors that place adolescent boys and girls at risk of leaving school early. Similarly, legislation and social assistance are just two of the tools that can be deployed to prevent dropout. Some programmes are intended to engage the community to identify children at risk of early school leaving. Others give children who have left school a second chance to complete basic education and obtain education qualifications, thus providing them with an opportunity to re-enter formal schooling.

Predicting which girls may be at risk of dropout and providing them with timely support is an essential but complex undertaking. The School Accountability for Girls Education project in Uganda, funded by the US Department of State and managed by World Vision in partnership with local NGOs, operated between 2016 and 2018 in 151 schools in 10 districts, targeting girls and young women aged 13 to 19 who had dropped out or were at risk of dropping out. It used a two-pronged strategy involving an early warning system and the engagement of Stay in School Committees to transform social norms and practices; reduce risk of early marriage, pregnancy, gender-based violence and HIV infection; and support girls to stay in school. The approach has also been used in Kenya, Mozambique and the Kingdom of Eswatini.

Second-chance programmes are crucial for young women who have missed out on education. They are typically delivered in non-formal settings and target underserved communities. The Advancing Quality Alternative Learning project, supported by Japan in partnership with Pakistan’s federal and provincial governments, is a non‑formal learning programme providing alternative education opportunities for disadvantaged groups, particularly girls and women. Promoting connections between literacy, life skills and vocational education, it aims to foster positive attitudes towards learning and education within families and communities. The project also works to strengthen non-formal education systems through policy development and by customizing standards, curricula, learning materials, data, monitoring, evaluation and assessment for adult literacy.

The next three priority areas in the questionnaire were related to policies to improve teaching and learning resources.

7 CURRICULUM AND TEXTBOOK REFORMS TO ELIMINATE GENDER BIAS AND STEREOTYPES

Relatively few interventions have been targeted at supporting curricular and textbook reforms. Under the UNESCO Malala Fund for Girls’ Right to Education, the Gender Equality and Girls’ Education Initiative in Viet Nam project (2015-2017) included a component on gender mainstreaming in curriculum and textbook development and teaching practices. In addition to contributing to development of the Action Plan on Gender Equality of the Education Sector for 2016-2020, the project aimed to influence attitudes to gender mainstreaming in curriculum and textbook development through substantive capacity development targeting curriculum developers, trainers, managers, education practitioners and students at all levels nationwide. Among the key results: The Ministry of Education and Training has developed a revised curriculum framework for primary and secondary education involving curriculum developers trained as part of the project. Revised curricula and textbooks will benefit over 15 million students and 850,000 teachers.

EU4Skills: Better Skills for Modern Ukraine is a programme funded by the European Union, Germany, Finland and Poland. Implemented by Germany’s GIZ development agency and KfW development bank, it runs from 2014 to 2020. The overall objective is to reform and modernize Ukraine’s TVET system so as to improve its quality and attractiveness for both female and male learners and increase its relevance to labour market needs, including overcoming gendered labour market segregation. Its activities include gender mainstreaming through gendersensitive, competence-based TVET curriculum standards applied to formal and non-formal vocational education and gender-responsive teaching, learning and assessment materials. It has also introduced gender-targeted interventions, such as accommodation and sanitation facilities for girls at vocational colleges and genderresponsive career guidance capacity development to overcome gender-segregated employment opportunities.

9 FEMALE TEACHERS IN RURAL AREAS

Countries use various strategies to improve the supply of rural teachers, including recruiting locally, providing financial incentives and improving working conditions. The Supporting Female Teachers to Teach in Rural Schools project in Malawi has been operating since 2010, supported by ActionAid, the Teachers’ Union of Malawi and community-based organizations. It has supported construction of houses for female teachers in rural areas, who act as role models and improve girls’ retention in school. Construction of each house is conditional on the local school management committee and other community members agreeing with district education officers that a female teacher will be posted to the school.

The Basic Education Support Programme is a multi-donor budget support programme in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, funded by the European Union, Australia and the United States in partnership with UNICEF; the WFP; the NGOs Plan International, World Vision, Save the Children and ChildFund; and the national Ministry of Education and Sports. It aims to improve pre-service and in-service training of primary teachers. The programme offers targeted scholarships for teacher training colleges to ethnic minority members. Of the 520 teachers trained to date, 70% have been female. Many of the teachers are deployed to remote villages.

11 SCHOOL-RELATED GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE

The French Ministry of Europe and Foreign Affairs funded the Fighting School-Related Gender-Based Violence project, implemented by UNESCO in partnership with UNICEF and Plan International, in Cameroon, Senegal and Togo between 2016 and 2018. In cooperation with the ministries of education and social protection, the project took a multisector approach, working both within and outside schools to implement various measures. It took steps to strengthen legal frameworks, internal regulations and official codes of conduct. It developed training programmes for the education community aimed at raising awareness of school-related gender-based violence and gender equality in schools. It involved pupils and community members and leaders via a participatory approach, conducting awareness-raising programmes on non-violence, children’s rights, gender equality and girls’ empowerment. And to measure the outcomes of violence prevention activities, it established mechanisms for data collection, reporting, referral and monitoring of gender-based violence, within and outside schools, through intersector coordination.

Under UNAIDS leadership, 21 eastern and southern African countries endorsed a Ministerial Commitment on Sexuality Education and Sexual and Reproductive Health Services in 2013. In 2016, a roadmap, regional accountability framework, civil society engagement strategy and youth accountability action plan were developed to help the East African Community and the Southern African Development Community track country progress and reach targets by 2020. With support from Sweden, UNESCO and its partners are promoting the realization of these targets through the 2018-2020 Our Rights, Our Lives, Our Future (O3) Programme, which aims to ensure the delivery of good-quality comprehensive sexuality education. It aims to reach 10.7 million students and 186,000 teachers between 2018 and 2020. An additional 30 million people are to be reached through community engagement and 10 million young people through social and new media platforms.

AID DIRECTED AT GENDER EQUALITY IN EDUCATION NEEDS TO LEAD TO SUSTAINABLE RESULTS

An emphasis on gender equality in aid programming is a good indicator of commitment, but it will not be sufficient to bring change. The broad selection of donor approaches to tackling challenges in girls’ education presented above is not intended to be representative of all interventions in the priority areas, nor is it necessarily indicative or suggestive of good practice in conception and/or implementation. To assess whether a donor project or programme applies good practice, projects need to be considered against criteria that might include: „„

- Whether they were effective in tackling one or more priorities with a proven positive impact on gender equality – for example, completion rates, number of qualified female teachers, improvement in learning outcomes

- Whether they were scalable and replicable in the sense that, while they may serve a particular context, they also have the potential in some form to address challenges on a larger scale as a government programme and/or in a different context „„

- Whether they were participatory in development or implementation, involving support by national and local authorities, civil society and community organizations, and the private sector.

For most of the interventions presented, assessing whether the criteria of effectiveness, scalability and participation were met would have been beyond the scope of this report. Access to information that could demonstrate whether interventions were designed so as to be scaled up and eventually implemented as national programmes is limited.

The design of gender equality-related interventions needs to include a clear plan for how they will effect change as they transition from a relatively small-scale, donor-led, implementer-controlled project to a government-led, fully resourced national programme. This involves not only an appropriate theory of change but also a wellthought- through practice of change. Considerations include the following:

- Has a plan been made for how the intervention will be picked up by government? Have sufficient negotiations been held between the donor, implementer and authorities? „„

- Can the programme’s cost per capita, which is inevitably higher in the pilot stage, be brought down to such a level that it would be plausible for the government to pick up the bill? „„

- Can the government realistically absorb the programme by activating existing budgetary and financing channels? „„

- Can the government realistically absorb the programme in terms of its administrative mechanisms, for example by ensuring appropriate oversight or training functions? „„

- Is the content of the programme sufficiently adapted to the realities of the country or would the intervention need to be adjusted further? Would that risk diluting its effectiveness? „„

- Does the programme have – and can the government continue applying – appropriate targeting tools to ensure that the interventions reach those most in need? „„

- Has a monitoring framework been established, enabling the collection of the right information on costs, implementation and results? „„

- Has a robust evaluation proved the merit of scaling up the project? Has this evaluation been sufficiently independent – and has it sufficiently considered the complications of scaling up – to ensure beyond doubt that the advice given to government is reliable?

Before a project can be considered ready for scaling up, these issues need to be scrutinized, since projects must compete with one another for limited resources. The current level of education financing in most countries concerned is not high enough to justify wasting donor or government resources – or to run the risk that projects will end when external financing runs out.