Target 4 C: Teachers

By 2030, substantially increase the supply of qualified teachers, including through international cooperation for teacher training in developing countries, especially least developed countries and small island developing States

CREDIT: Heather Perry/UNHCR. Ekhlas is a refugee who was forced to flee the outbreak of civil war in Sudan with her mother, father and three younger brothers in 2003 and who has become an English Language Learner teacher in Portland, Maine.

Key Messages

- Internationally comparable data on teacher indicators remain surprisingly scarce. Relatively few countries report even a basic headcount of teachers, and that does not take teaching hours, teachers in administrative positions and other complexities into account.

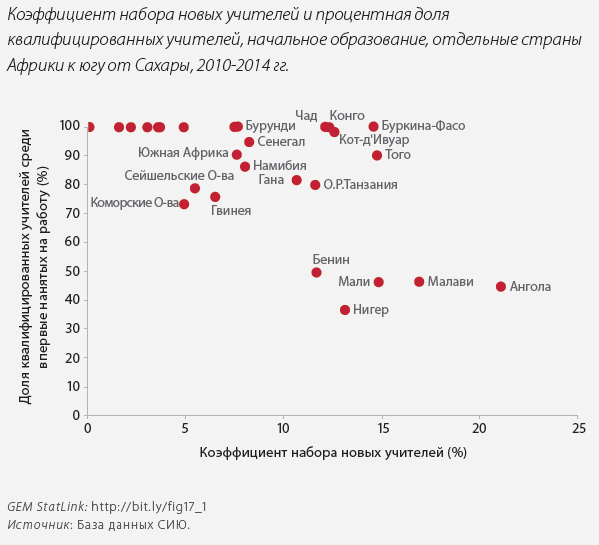

- Using national definitions, 85% of primary teachers globally were trained in 2017, a decline of 1.5 percentage points since 2013. Only 64% of primary teachers were trained in sub-Saharan Africa, where some countries’ ability to maintain entry standards while recruiting teachers at high rates is stretched. In Niger, 13% of primary teachers were newly recruited in 2013, one of the highest rates, but only 37% of them were trained.

- Only 51% of countries have the minimum data to estimate teacher attrition rates. Moreover, available data are not always straightforward to interpret. They may refer only to public schools, as in Uganda, or may cover regions without accounting for cross-regional mobility, as in Brazil.

- Caution is needed in interpreting attrition estimates. Monitoring individual teachers in Australia, revealed that 83% of those who left returned within two years, at least half of them from paid leave.

- International teacher migration can improve teacher access to professional development opportunities and host countries’ teaching force diversity. But it can also result in sending systems and migrating teachers suffering losses. Regulations and monitoring of recruitment, hiring and working conditions are needed to protect them.

Gathering internationally comparable data on teacher-related indicators remains challenging. Relatively few countries generate comparable data, especially for secondary education, even using the most basic definition of the teacher headcount, which ignores number of teaching hours and number of teachers in administrative positions.

Low and lower middle income countries continue to suffer severe shortages of trained and qualified primary school teachers. Some sub-Saharan African countries have high recruitment rates, potentially undermining entry standards if teacher education capacity is limited. In Niger, where 13% of primary teachers were newly recruited in 2013, only 37% of them were trained (Figure 16).

Figure 16: Teacher education standards are difficult to maintain with higher recruitment rates

High recruitment rates do not just indicate education expansion; they may be necessary to replace departures. Reliable data on attrition are patchy and hard to interpret. Accurate estimates require personnel data that assign identification numbers, so individuals can be traced as they qualify, enter, exit and re-enter the profession. Data should distinguish among various leavers and entrants, including re-entrants. Monitoring attrition requires a national system and information on all types of schools in systems with diversified provision, but often the information available is only local (e.g. Brazil) or concerns only public schools (e.g. Uganda).

Research from countries including Chile, Sweden and the United States found higher attrition among teachers who were less experienced, more qualified (and therefore more employable elsewhere), placed in more challenging or rural schools, inadequately paid or on short-term contracts. However, evidence from longitudinal studies in Australia implied that most teachers who appeared to have left did so for family reasons and returned to the profession within two years.

Previous year’s Target 4.C