Education and the other SDGs

This report examines how education can accelerate achievement of the SDGs related to decent work, sustainable cities and justice in different ways, including through developing professional capacity.

CREDIT: Reginald Louissaint Jr./Save the Children. Esther, a nurse at Dispensaire St. Paul de Moulines in Grand’Anse Department of Haiti, counsels women about family planning.

Many countries have fewer adequately trained social workers than needed to achieve SDG 8 on decent work and economic growth. In Ethiopia, 60% of public-sector social workers interviewed said they lacked relevant education. Some countries are increasing training efforts: China aims to have 230,000 new social workers by 2020. In South Africa, the number of social workers increased by 70% between 2010 and 2015.

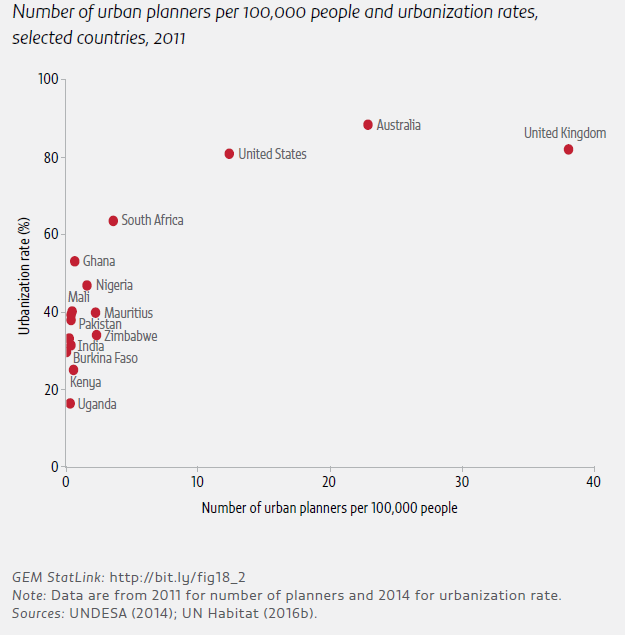

With over half the world’s population living in cities, achieving SDG 11 on sustainable cities and communities requires urban planners to improve informal settlements and prepare for future increases. Many countries face acute shortages of planning professionals (Figure 17). India needs 300,000 town and country planners by 2031; in 2011, it had about 4,500. Planning programmes need to integrate physical, environmental and social planning, including education. Local officials in countries including Malawi, Mozambique and Namibia need to improve planning capacities.

Figure 17: There are too few urban planners in Africa and Asia

To achieve SDG 16 on peace, justice and strong institutions, law enforcement officers’ education requirements and training need to improve so as to help build trust and reduce bias and use of force. In the United States, average police training lasts 19 weeks, compared with 130 weeks in Germany. Only 1% of US police departments require a four-year university degree; officers with university degrees were less likely to use force. Some countries, including Singapore, have used training to curb police corruption; others, such as Indonesia, have collaborated with international partners to enhance police professional capacity.

An estimated 4 billion people worldwide lack access to justice, implying a need to build legal capacity. Judicial education varies among countries. Training typically lasts three to five years, but a law degree is not always a prerequisite for becoming a judge, even in high income countries. Some countries, including France, provide substantial initial professional training once judges are selected. Countries such as Ghana and Jordan have continuing education institutions for judges.

Previous Years