Mobility of students and professionals

In an increasingly globalized world, young people study abroad and skilled professionals follow employment opportunities across borders to pursue their talents. Skilled mobility has significant benefits, costs and risks for individuals, institutions and countries.

CREDIT: Fàbio Duque Francisco/GEM Report. A Romanian Erasmus student in Lisbon: ‘My time in Lisbon helped me learn to be more tolerant, and to look past stereotypes’.

Internationalization of tertiary education takes many forms

Internationalization of tertiary education includes ‘policies and practices undertaken by academic systems and institutions – and even individuals – to cope with the global academic environment’. It encompasses movement of students and faculty, as well as courses, programmes and institutions affecting education at home and abroad.

Half of all international students move to five English-speaking countries: Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States. The shares of international students in France and Germany have grown to 8% and 6%, respectively, in part because they increasingly offer postgraduate programmes in English. China, India and the Republic of Korea accounted for 25% of all outbound mobility in 2016. Europe is the second-largest sending region, accounting for 23% of the total in 2016, but 76% of the 0.9 million mobile European students stay within the region.

Students decide where to pursue tertiary education based on availability of places at the best home universities, ability to pay and relative quality of education at home and abroad. Policies governing students’ ability to work can also be a driver. In 2011–2014, Indian student numbers in the United Kingdom fell by nearly 50% after policy changes limited post-graduation work visas; meanwhile their number rose by 70% in Australia and 37% in the United States. Some countries, including China and Germany, try to retain international students in their labour markets to fill local skills gaps.

For universities, revenue raising is the main driver of international student recruitment. In 2016, international students brought an estimated US$39.4 billion into the US economy. In several Asian countries with declining birth rates and ageing populations, such as Japan, the tertiary education sector is turning to international students to keep institutions open.

Mexico and the United States are among countries that use mobility programmes as cultural diplomacy and development aid. Some sending countries, including Brazil and Saudi Arabia, subsidize study abroad as a development strategy.

Internationally mobile faculty may be academics sought by elite universities, academics hired to fill local gaps or ‘transient academics’ continuing their careers in the countries where they obtained their doctorates. Institutional mobility may cause traditional student mobility to decline but serve more students with varying education needs. Massive open online courses expand access to education, particularly in the developing world. Offshore, cross-border and borderless programmes, including branch campuses and regional education hubs, enable international education at home.

Harmonizing standards and recognizing qualifications facilitates internationalization of tertiary education

To facilitate student mobility, institutions may engage in complex relationships and agreements, e.g. dual and joint degree programmes, credit transfers, strategic partnerships and consortia. Increasingly, countries attempt to harmonize standards and quality assurance mechanisms at the bilateral, regional or global level.

The introduction of common degree standards, quality assurance, qualification recognition mechanisms and academic mobility exchange programmes enabled Europe and partner countries to establish a European Higher Education Area (EHEA) in 2010. It was the culmination of the Bologna Process, launched in 1999, involving the European Commission, the Council of Europe and representatives of tertiary education institutions, quality assurance agencies, students, staff and employers from, currently, 48 countries. The Lisbon Recognition Convention governs recognition of qualifications between EHEA countries and has been ratified by 53 countries.

Other regions are working to emulate these initiatives, including the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the East African Community. At the third Regional Conference on Higher Education, countries in Latin America and the Caribbean agreed to strengthen regional integration in tertiary education. To build on such initiatives, UNESCO has drafted a Global Convention on the Recognition of Higher Education Qualifications for ratification in 2019.

STUDENT EXCHANGE PROGRAMMES IN EUROPE OFFER LESSONS FOR SOUTH-EASTERN ASIA

Institutionalizing student exchange programmes at the regional level greatly expands opportunities for short-term student mobility. Under the Erasmus programme, established in 1987 and expanded as Erasmus+ in 2014, participating students study 3 to 12 months in another European country, and home institutions apply this time towards their degrees. It aims to enhance participants’ intercultural awareness, skills and employability and promote social cohesion in Europe.

Some 9 out of 10 participants reported that it increased their resilience, open-mindedness and tolerance. There is evidence indicating that European student mobility increased employability. However, evaluations using longitudinal data that control for determinants of student mobility provide a more nuanced picture with respect to equity. About 4.4% of UK students with professional parents participated in Erasmus+ in 2015/16, compared with 2.8% with low-skilled parents. This gap has increased over time.

In 2015, ASEAN and the European Union launched the EU Support to Higher Education in the ASEAN Region (SHARE) programme to support harmonizing regional tertiary systems. Obstacles to increased mobility are resulting from lack of concerted effort among regional stakeholders. Unlike in Europe, credit transfer systems vary widely among ASEAN countries.

Recognizing professional qualifications maximizes the benefits of international labour mobility

Recognizing professional qualifications facilitates and maximizes the benefits of skilled labour migration. In OECD countries, over one-third of immigrants with tertiary education are overqualified for their jobs, compared with one-quarter of natives. In the United States, forgone earnings of underemployed immigrant college graduates could represent US$10.2 billion in lost tax revenue annually.

But recognition systems are often too underdeveloped or fragmented to meet migrants’ needs. Processes are complex, time-consuming and costly, so often only a minority apply. To improve effectiveness, assessment agencies, licensing bodies and academic institutions can harmonize requirements and procedures. Governments can ensure agencies abide by fair, transparent procedures and adhere to best practices. Establishing legal rights to recognition can also improve uptake and efficiency, as in Denmark. A 2012 law in Germany enables foreign nationals to gain recognition regardless of residence status or citizenship.

When their qualifications are not recognized, migrants cannot legally practise in regulated professions, such as teaching and nursing, despite vacancies in many destination countries. Partial recognition can help. Applicants may have to pass an examination, work under supervision for a period or refrain from performing certain functions. The EU Professional Qualifications Directive allows certain groups of professionals with approved qualifications to practise across the EU. Establishing and maintaining such automatic recognition requires substantial political commitment and resources, so similar agreements are few.

TEACHER MIGRATION BRINGS BENEFITS AND RISKS

Teachers may be motivated to migrate by low pay, unemployment, political instability, poor working conditions and lack of infrastructure. But teaching is frequently a regulated profession subject to national qualification requirements that challenge migrants.

Since regulations on teacher qualifications often relate to language skills, many large flows are between countries with linguistic and cultural commonalities. Teachers from Egypt and other Arab countries, attracted by high salaries, helped scale up education systems in the Gulf Cooperation Council states. Now countries are replacing Arabic with English as the language of instruction, and English-speaking recruits are replacing Egyptian and Jordanian teachers.

Teacher migration can create domino effects of teacher shortages in countries of origin. For instance, the United Kingdom recruits teachers from countries such as Jamaica and South Africa. In turn, facing its own teacher shortages, South Africa recruits teachers from abroad, especially from Zimbabwe. Caribbean countries have also experienced high teacher emigration in recent decades, not least due to active UK and US recruitment efforts.

The loss for sending countries can be substantial, both in terms of investment in teacher training and education and for the education system as a whole. This concern has motivated international initiatives that recognize sending countries’ interests, such as the Commonwealth Teacher Recruitment Protocol. However, as a non-binding code of conduct, the protocol does not constrain individual teachers who wish to emigrate.

International teacher recruitment is a lucrative business that attracts commercial agencies. They are rarely closely regulated and may charge high placement fees or provide inadequate information, prompting calls for recruiter registration in sending and receiving countries.

LOSS OF TALENT CAN BE DETRIMENTAL FOR POORER COUNTRIES

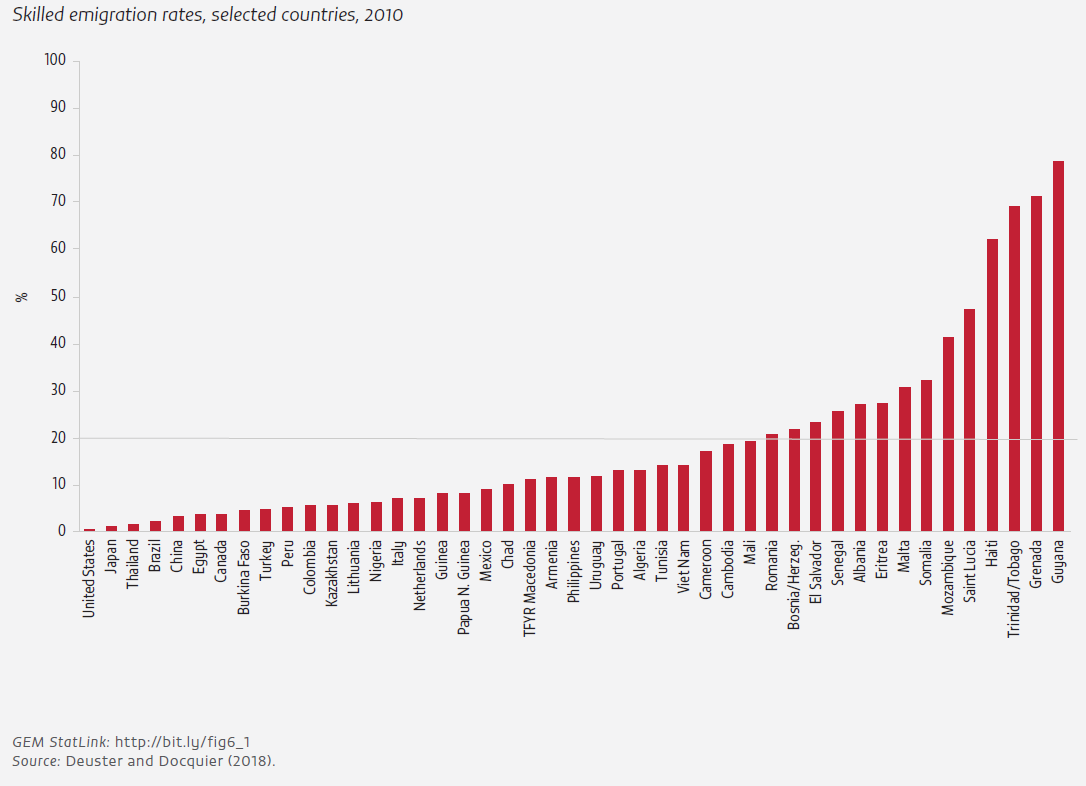

Emigration rates of the highly skilled are above 20% in just over one-quarter of 174 countries and territories, including Grenada and Guyana in Latin America and the Caribbean, Albania and Malta in Europe, and Eritrea and Somalia in sub-Saharan Africa (Figure 5).

Richer countries actively compete for skilled workers, leading to concerns that emigration could impede development in sending countries due to loss of skills. However, apart from the effect of remittances, the very prospect of skilled emigration can also spur education investment in sending countries. Analysis for this report shows that a high-skilled migration rate of 14% generates the highest positive effects on human capital accumulation. After accounting for the characteristics of origin and destination countries, emigration prospects generate net brain gain in 90 out of 174 countries.

Some countries, especially in Asia, are seeing more citizens return with valuable skills. The Philippines has instated policies for returnees and linked them to recognition services and prospective employers.

Figure 5: In several countries, more than one out of five highly skilled people emigrate

TECHNICAL AND VOCATIONAL EDUCATION IS A TOOL FOR MIGRANTS AND REFUGEES

Two concerns affect technical and vocational education and training (TVET) programmes for migrants and refugees.

First, many barriers reduce migrant and refugee demand for skills development through TVET. Initial unemployment and precarious employment in ill-matched jobs lower migrants’ return on investment in their skills. Undocumented migrants and asylum-seekers may not have the legal right to work, as in Ireland and Lithuania, discouraging participation in vocational training. Multiple providers and entry points can make navigating TVET systems difficult. Yet TVET providers and public employment services can connect migrants with relevant employers to help them gain work experience. ‘Welcome mentors’ in Germany support small and medium-sized enterprises in recruiting skilled workers from among new arrivals; in 2016, 3,441 refugees were placed in training.

Second, not recognizing prior learning compromises refugees’ ability to get decent work or further education and training. Migrants and refugees are unlikely to carry qualifications and certificates with them, and TVET degrees may be less portable than academic degrees because of the greater variability among vocational education systems. In 2013, Norway introduced the Recognition Procedure for Persons without Verifiable Documentation. More than half the refugees whose skills were recognized in 2013 either found a related job or entered further education. Recognition, validation and accreditation can also be facilitated by intergovernmental cooperation. National recognition agreements exist between the Syrian Arab Republic and Egypt, Iraq, Jordan and Lebanon.

Previous year