Internal migration

An estimated 763 million people live outside the region where they were born. Among a variety of possible movements, permanent or temporary, between or within urban and rural areas, it is rural to urban flows and seasonal or circular flows that tend to pose the biggest challenges for education systems.

CREDIT: Louise Dyring Mbae/Save the Children. Zie is an 11-year-old boy in grade 5 who has lived at a boarding school in Weishan county, People’s Republic of China.

While major rural to urban migration accompanied the economic growth of the 19th to mid-20th century in high income countries, the largest internal population movements today occur in middle income countries, particularly China and India. In sub-Saharan Africa, rural to urban migration has also made urban development planning challenging.

Migration rates vary by age but tend to peak among people in their 20s. From an education perspective, internal migration affects relatively few primary school-age children and slightly more secondary school-age youth. But education of better quality in urban areas is a prominent reason for migration among younger people. In Thailand, 21% of youth said they migrated for education.

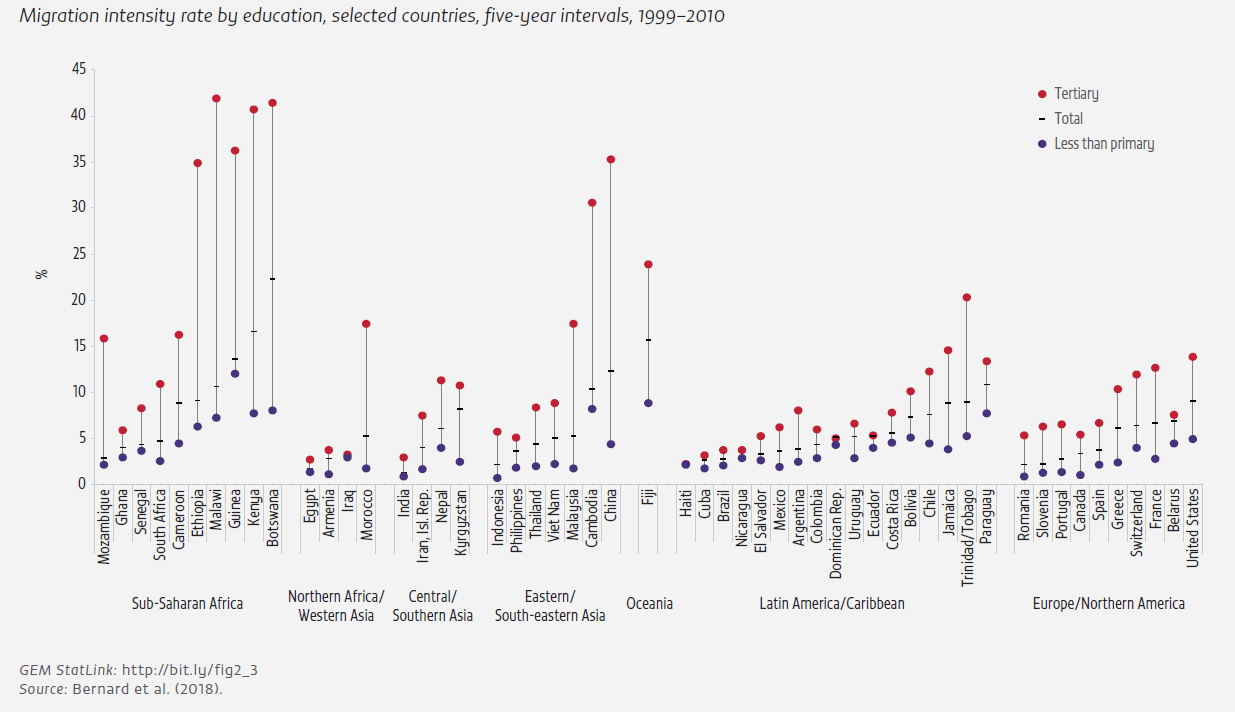

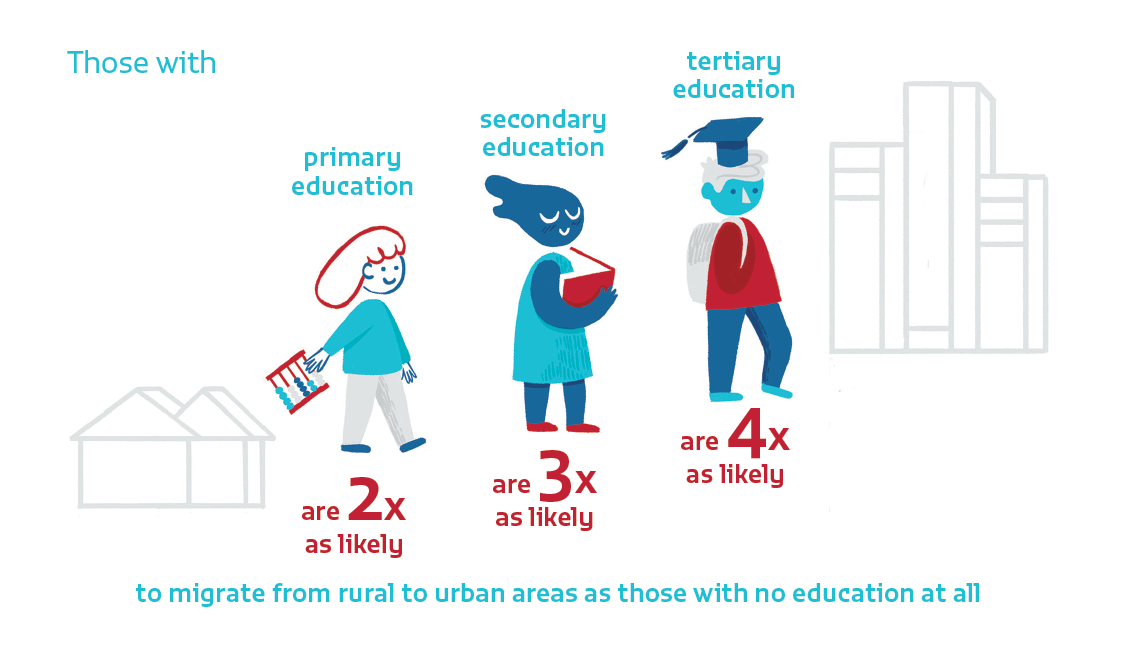

The more educated are more likely to relocate on the prospect of higher returns on their education elsewhere (Figure 1). Preferences and aspirations as a result of education also prompt people to leave rural areas irrespective of earning potential. Across 53 countries, the probability of migration doubled among those with primary education, tripled among those with secondary and quadrupled among those with tertiary, compared with those with no education.

Figure 1: The more educated are more likely to migrate

Migration improves education outcomes for some but not all

Rural to urban migration can increase educational attainment in countries where access to education in rural areas is low. Among a group born in selected rural districts in Indonesia, those who migrated to a city as children attained three more years of schooling than those who did not.

Yet migrant children may not enjoy the same education outcomes as their peers. In Brazil, among adolescents born in 2000/01 in the Northeast region, those who migrated during secondary school had worse progression rates than those who stayed. Educational opportunities of children affected by internal migration may be compromised for several reasons, from precarious legal status to poverty, inadequate government attention, or biases and stereotypes.

INTERNAL MIGRATION CONTROLS AFFECT EDUCATION ACCESS

In many countries, fears of unsustainable urbanization and rural–urban imbalances have prompted policies to curb migration, which can affect migrants’ access to education in some cases. Viet Nam’s ho-khau system restricted migrants’ access to public education, and poor rural to urban migrants moved to areas underserved by public schools. Recent reforms aim to abolish restrictions, but the legacy of past policies still disadvantages migrants with temporary status.

China’s hukou registration system, which linked access to services to registered place of birth, excluded children of rural migrants from public schools. Significant revisions have taken place in recent years. The government required local authorities to provide education to migrant children in 2006. It abolished public school fees for rural migrant children in 2008 and started decoupling registered residence from access to services in 2014. Since 2016, it has been asking all but the largest cities to ease restrictions further.

However, barriers to education persist for migrants. Paperwork and other admission requirements can limit access. In Beijing, migrants need five certificates to enrol in public school. Teachers can have discriminatory views of migrant youth. Teachers in unauthorized migrant schools may suffer lower pay and lack job security, and parents frequently complain about teacher quality in these schools.

CHILDREN LEFT BEHIND FACE PARTICULAR EDUCATION CHALLENGES

Migration also affects the education of millions of children left behind with one parent or other family members. In Cambodia, children left behind, especially girls, were more likely to drop out.

The China Family Development Report 2015 estimated the percentage of left-behind rural children at 35%. Evidence on migration’s effect on the education and well-being of children left behind is mixed. Some studies show a positive impact on performance, but others show left-behind children have lower grades and more mental health problems than their peers.

Since 2016, China has instated policies aimed at improving care for left-behind children, including calling on local governments to urge parents to appoint a guardian for left-behind children. Boarding schools are a key strategy, but they are often understaffed and underequipped. Better management training for administrative staff is needed to improve child welfare.

Statistics on boarding schools and students are lacking, although such schools are prevalent in some countries. In Uganda, the share of students boarding hovers at around 15% up to age 13, rising to 40% in the final years of upper secondary education.

SEASONAL LABOUR MIGRATION AFFECTS EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES

Seasonal migration, which is a survival strategy for the poor, can disrupt education and expose children to child labour and workplace hazards. In India, a study showed that about 80% of temporary migrant children in seven cities lacked access to education near work sites, and 40% worked, experiencing abuse and exploitation. Recent initiatives by India’s national government aim to ensure school attendance by migrant children by encouraging flexible admission, providing mobile education and improving coordination between sending and receiving states, but there have been many implementation challenges. A pilot programme in Rajasthan state in 2010–2011 at brick kiln work sites saw rampant teacher and student absenteeism due to poor teaching and learning conditions and the need for students to work.

CHILD DOMESTIC WORKERS ARE VULNERABLE TO EXCLUSION FROM EDUCATION

In 2012, around 17.2 million children aged 5 to 17 were in paid or unpaid domestic work in an employer’s home. Two-thirds were girls. Young girls, for instance in Lima, view domestic work as a way to leave rural areas and continue education, but their workload often ends up preventing their participation.

Fostering is a common strategy in many African countries. Nearly 10% of Senegalese children were fostered. While boys were more likely to be sent to households placing greater emphasis on education, ending up more educated than their siblings, girls were almost four times more likely to help with host household chores and were less likely to be hosted for education reasons.

In 2012, around 17.2 million children aged 5 to 17 were in paid or unpaid domestic work in an employer’s home

NOMAD AND PASTORALIST EDUCATION NEEDS ARE NOT ADDRESSED

Mobility is an intrinsic part of life for nomads and pastoralists, and interventions must recognize their needs. Their enrolment tends to be low, with significant seasonal fluctuation, and students struggle to develop literacy and numeracy skills at the same pace as their peers. In Mongolia, underfunding has weakened the soum boarding schools that catered to the nomadic population, resulting in learning disparities between nomadic and non‑nomadic children.

Many countries with significant nomadic or pastoralist populations have dedicated government departments, commissions or councils, such as the Department of Education for Nomads in Sudan. Efforts focus on adjusting education to seasonality and mobility; examples are residential schools and mobile schools. In northern Nigeria, many almajiri (‘migrant pupils of Islamic knowledge’) are nomadic pastoralists. In Kano state, an intervention targeting 700 traditional teachers focused on engaging with the community and collaborating to select teachers of non-religious subjects.

A network of schools that students could exit and enter at any time or place might be a viable solution but would require efficient and effective tracking systems. Some countries, including Kenya and Somalia, have made teachers more mobile, travelling with nomads to deliver education.

Education for nomadic populations should recognize and value their way of life. Vocational education for a nomadic lifestyle can be particularly relevant to pastoralists. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations has worked with nomadic communities on pastoralist field schools in Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya, South Sudan and Uganda since 2012, with courses focusing on livestock management efficiency and mitigating effects of climate change.

INDIGENOUS GROUPS STRUGGLE TO PRESERVE THEIR IDENTITY IN CITIES

In many places, education for indigenous people has involved forced assimilation through schooling. This legacy is compounded by poverty and migration to urban areas, which often implies further cultural erosion, language loss and discrimination. Loss of language is a major issue for urban indigenous populations. Younger generations in cities in Ecuador, Mexico and Peru are significantly less likely to speak indigenous languages than their rural counterparts.

Regulatory frameworks on indigenous rights make little reference to indigenous people living in cities. Over 50% of Canada’s indigenous population live in cities. Analyses of urban aboriginal populations showed the importance of education in improving their quality of life and found that incorporating culturally appropriate curricula and practices improved early childhood education outcomes.

Migration challenges education planners in villages and cities

Rural depopulation means education planners, particularly in high income countries, must balance efficient resource allocation with the welfare of affected communities. Finland closed or consolidated almost 80% of schools with fewer than 50 students – more than 1,600 in all – between 1990 and 2015. Urbanization and reduced fertility present similar challenges in many middle income countries. The number of rural schools in the Russian Federation fell from 45,000 to fewer than 26,000 between 2000 and 2015. In China, the number of rural primary schools decreased by 52% between 2000 and 2010.

In considering school consolidation to increase efficiency, governments must recognize the important social role schools play in communities, as well as other benefits. Analysis of data from the 2015 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) showed that students from smaller schools had fewer disciplinary, tardiness and absenteeism issues.

Successful consolidation requires consultation with all parties affected and consideration of costs. The Lithuanian government developed priority measures to preserve small rural primary schools and provided safe transport with hundreds of new buses.

Some countries encourage rural schools to share resources and learning in order to stay vibrant. Chile has 374 micro-centres for rural teachers to meet and discuss common challenges. Since 2011, the Chinese government has engaged in major renovation and upgrading of small rural school facilities, and non-government organizations (NGOs), local communities and schools have established resource-sharing networks.

MIGRANTS IN SLUMS HAVE FEWER EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES

At least 800 million people live in slums. National definitions or estimation methodologies may underestimate the numbers. Many slum dwellers are rural to urban migrants and lack access to basic services, including public education. Eviction and resettlement of slum dwellers raises dropout rates and lowers attendance. In Bangladesh in 2016, the rate of secondary school-age adolescents out of school was twice as high in slums as in other urban areas.

Education in slums is not a data collection priority, since urbanism debates focus on housing and water and sanitation challenges. The Shack/Slum Dwellers International network collects data in over 30 countries, but its education data are limited. Education activity in slums may be underestimated because of unregistered private schools, which make up for the lack of public schools. In Kibera, Kenya, an open mapping project found 330 schools, while the official estimate was 100. Often the only option in slums, private schools tend to be poorly regulated and employ untrained educators. An initiative to raise teacher quality in Nairobi slums improved student literacy and numeracy outcomes.

Education needs to be a priority in urbanism debates concerning slums. Securing dweller tenure and establishing rights are key steps towards education provision, as governments are often reluctant to invest in education infrastructure for people who settled on land they did not own. In Argentina, access to land titling was associated with long-term education improvement. Rigid registration and documentation requirements often hinder migrant participation in social protection programmes that could benefit their education. In Kenyan slums, the urban social protection programme required national identification, thus precluding the 5% of preselected recipients who were refugees, unable to prove Kenyan nationality or from child-headed households.

Previous year