Diversity

Education that values diversity is important for all countries, enabling them to build inclusive societies in which differences are appreciated and respected and good-quality education is provided for all.

CREDIT: IOM Greece. ‘I love school, efcharisto!’ says 7-year-old Roham from Tehran, moments before taking the bus to the primary school.

Migrants and refugees are sometimes judged on the basis of perceptions of their group identity rather than personal qualities. Particularly if they differ visibly from host populations, they may be viewed as ‘other’, and stereotypes and prejudice may lead to discrimination, including exclusion from good-quality education.

Prejudice and discrimination are present in many education systems, despite policies against them. Structural discrimination against students from immigrant families in the United States includes lack of bilingual programmes for young children and literacy tests not given in home languages.

Public attitudes shape immigrants’ self-perception and well-being. Perceived discrimination is associated with depression, anxiety and lower self-esteem. Immigrants are less likely than natives to see themselves as belonging to the host country, according to the 2014 World Values Survey.

Education influences attitudes towards immigrants and refugees

Education level is associated with attitudes towards immigrants. More educated people were less ethnocentric, valued cultural diversity more and viewed migration’s economic impact more positively. Research showed that those with tertiary education were two percentage points more tolerant than those with secondary education, who, in turn, were two percentage points more tolerant than those with primary education. Younger people, especially the highly educated, also tend to have more positive attitudes towards immigration.

Negative media portrayals of immigrants and refugees can reinforce prejudice. Media coverage of migration and displacement issues is increasingly negative and polarized, as seen, for instance, in Canada, the Czech Republic, Norway and the United Kingdom, where the media often portray immigrants and refugees as a threat to culture, security and the welfare system. Migration-related media stories are often stereotypical, omitting immigrant or refugee voices and using imprecise terminology. Education can mediate negative media portrayals by providing political knowledge and critical thinking skills to decipher fact from fiction.

Education can mediate negative media portrayals by providing political knowledge and critical thinking skills to decipher fact from fiction

Inclusion should be at the centre of education policies and systems

Countries use different approaches to address diversity in education systems: assimilation, multiculturalism/ integration and interculturalism/inclusion. Assimilation can be detrimental to migrant identity. Interculturalism, by contrast, helps students learn not only about other cultures but about structural barriers in host countries that perpetuate inequality.

A few countries have specific policies on multicultural or intercultural education. Ireland, where immigrant children represented 15% of the population under 15 in 2015, developed the Intercultural Education Strategy 2010–2015, aimed at developing provider capacity, supporting language proficiency, encouraging partnerships with civil society and improving monitoring. Further legislation removed barriers, banning fees and requiring schools to publish admission policies. A European Parliament study found that Ireland and Sweden had Europe’s strongest monitoring and assessment frameworks for immigrant education.

Political influences can undermine intercultural education policies. In the Netherlands, deteriorating attitudes towards immigrants have fostered an integration policy focused on loyalty to Dutch society, with intercultural education being replaced with citizenship education.

Another dimension in the development of immigrant students’ sense of belonging is diaspora schools that maintain links with the country of origin. These may range from schools managed or coordinated by the government of the home country, as in the case of Poland; private schools established by immigrant communities, as in the case of Filipinos in Saudi Arabia or Brazilians in Japan; and non-formal schools, transmitting the linguistic and cultural heritage of the home country.

CURRICULA AND TEXTBOOKS ARE BECOMING MORE INCLUSIVE

Curricula and textbooks can reduce prejudice and develop migrants’ sense of belonging. Learning about other countries’ histories was associated with positive attitudes towards endorsing rights of ethnic groups in 12 out of 22 countries that took part in the 2016 International Civic and Citizenship Education Survey.

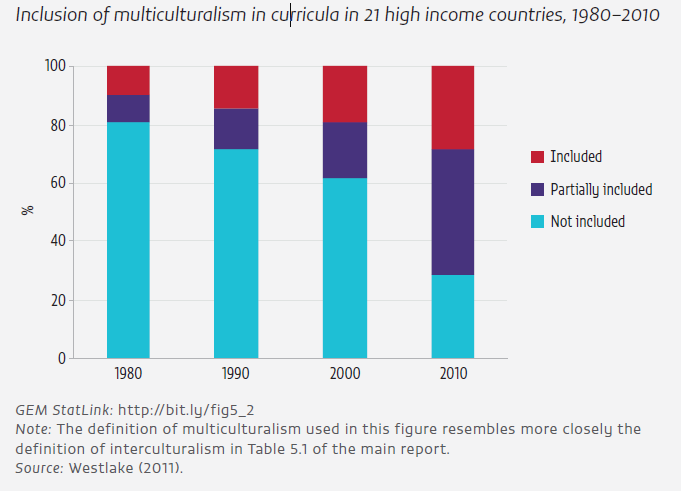

More countries are modifying curricula to reflect growing social diversity. Among 21 high income countries analysed for a policy index on multiculturalism, only Australia and Canada included multiculturalism in curricula in 1980. By 2010, multiculturalism was somewhat on the agenda in over two-thirds of countries and fully integrated in an additional four countries, Finland, Ireland, New Zealand and Sweden (Figure 4).

In 2015, 27 out of 38 predominantly high income countries provided intercultural education as a stand-alone subject, integrated it into the curriculum, or both. Multicultural and intercultural values can be incorporated into individual subjects. History curricula are often ethnocentric, but other subjects differ, such as geography in Germany and citizenship in England (United Kingdom). Some modern textbooks continue to omit contentious migration-related issues. In Mexico, textbooks do not discuss undocumented migrants and the relationship with the United States. However, textbooks in Côte d’Ivoire discuss refugees and displacement, prominent since the political crisis in 2002.

Curricula can be adapted locally, as in Alberta, Canada, where teaching resources support immigrant and refugee instruction and learning, focusing on specific communities, such as the Karen, Somalis and South Sudanese. Strong school leadership can also help. In the United States, where school leaders value diversity, students are more likely to engage in intercultural interaction.

Teaching needs to incorporate activities that promote openness to multiple perspectives to help students develop critical thinking skills. Experiential and cooperative learning can help improve intercultural relations, increase acceptance of difference and reduce prejudice.

Figure 4: An increasing number of countries include multiculturalism in curricula

TRAINING THAT PREPARES TEACHERS FOR DIVERSE CLASSROOMS IS NOT MANDATORY IN MOST COUNTRIES

Teachers need support to teach diverse classrooms, but 52% of teachers interviewed in France, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Spain and the United Kingdom felt inadequately supported from management in managing diversity. The extent to which teacher education includes diversity varies by country. In the Netherlands, New Zealand and Norway, teacher candidates take mandatory courses in supporting students from diverse backgrounds. Completion of such courses is usually optional in Europe.

Teacher education programmes tend to emphasize general knowledge over practical pedagogy. A survey of 105 programmes in 49 countries found that only one-fifth prepared teachers to anticipate and resolve intercultural conflicts or understand psychological treatment and referral options available for students in need. In-service teachers need continuing professional development in this respect. The 2013 OECD Teaching and Learning International Survey found that only 16% of lower secondary teachers in 34 education systems had undertaken multicultural or multilingual education training in the preceding year.

There are few studies on the impact of teachers with immigrant backgrounds, and those that exist may not distinguish between first- and subsequent-generation immigrants or between immigrant and minority teachers. Some evidence suggests that diversity among teachers is associated with immigrant student achievement, self-esteem and sense of safety. However, teachers with immigrant backgrounds are under-represented relative to student body composition in Europe. Discriminatory policies in entering the profession and bias in hiring partly fuel this shortage.

EDUCATION HAS A ROLE IN PREVENTING VIOLENT EXTREMISM

While violent extremism, terrorist attacks and state and non-state civilian targeting undoubtedly directly cause migration and displacement, public opinion in high income countries has come to overemphasize the reverse, associating migration with terrorism. Yet any such relationship is very tenuous; attacks by foreigners represent a fraction of those by nationals and pathways to radicalization can take numerous forms.

Preventing the emergence of extremism is a key line of defence against terrorism. Extremists tend to instrumentalize development challenges or exacerbate them to create and exploit a vicious circle of marginalization, particularly affecting the poorest and most vulnerable.

By promoting respect for diversity, peace and economic advancement, education can be a buffer against radicalization. Violent extremists often see education as a threat and target schools for attacks, as with the Boko Haram attacks in Nigeria.

Conversely, exclusion from education can increase vulnerability to radicalization. Exclusion from the benefits of education is equally harmful. In eight Arab countries, unemployment increased the probability of radicalization among the more educated whose expectations of economic advancement had been disappointed.

Many countries include efforts to prevent violent extremism in curricula, but teaching materials do not always match. Worldwide, 1 out of 10 relevant textbooks covers prevention of armed conflict or discusses conflict resolution or reconciliation mechanisms – a small increase since the 1950s.

Teachers can foster tolerant attitudes but need adequate training. Pedagogical methods, such as peer-to-peer learning, experiential learning, teamwork, role play and other approaches that stimulate critical thinking and open discussion, are most effective. At the same time, teachers should not have to police their students or limit personal freedoms in the pursuit of security.

Schools can be convenient sites for violent extremism prevention initiatives involving stakeholders outside education. Some programmes, including in Indonesia, use victims’ voices to make topics more relevant and salient to students. Education against violent extremism should be gender-sensitive and engage women and girls. Women sometimes lead such education initiatives. For instance, in Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, a women’s organization has taught mediation and conflict transformation skills to 35,000 women and 2,000 youth.

By promoting respect for diversity, peace and economic advancement, education can be a buffer against radicalization

Non-formal education has a critical but neglected role in building resilient societies

Education and awareness-raising about migration and displacement issues also take place outside school walls. Non-formal education has many forms and purposes. Unfortunately, as governments are rarely the provider, little systematic information on it is available.

Community centres play a key role in non-formal education on migration. In Turkey, the NGO Yuva Association offers language courses and skill workshops through community centres. Cultural facilitators or brokers can offer translation services and help in navigating the education system. Sweden’s Linköping municipality trained tutors with knowledge of Somali or Arabic to act as ‘link people’ for its Learning Together programme. Cities can lead education efforts against xenophobia, as in São Paulo, Brazil, but should involve immigrant communities to be successful.

Art and sports are powerful media for non-formal education. Community festivals in Norway and Spain provide space for intercultural exchange. South Africa’s Kaizer Chiefs football team has driven a social media campaign highlighting foreigners’ positive contribution to the country.

Previous year