Displacement

The number of displaced people is at the highest level since the end of the Second World War. Displaced people tend to come from some of the poorest and least-served parts of the world, and their vulnerability is exacerbated when displacement deprives them of education.

CREDIT: Petterik Wiggers/UNHCR. Refugee children from Ethiopia and Somalia attend schools in a refugee camp close to the Djibouti-Somalia border.

There are 19.9 million refugees under the protection of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), of whom about 52% are under 18. There are 5.4 million Palestine refugees under the protection of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). Around 39% of refugees live in managed, self-settled or transit camps or collective centres, mostly in sub-Saharan Africa. The majority of the rest live in individual accommodation in urban areas.

In addition, conflict has left 40 million internally displaced people (IDPs), the greatest number living in the Syrian Arab Republic, while an additional 19 million have been displaced by natural disasters, with China hosting the largest population.

The vulnerability of forcibly displaced people is further exacerbated when they are deprived of an education

Education for the displaced lags in access and quality

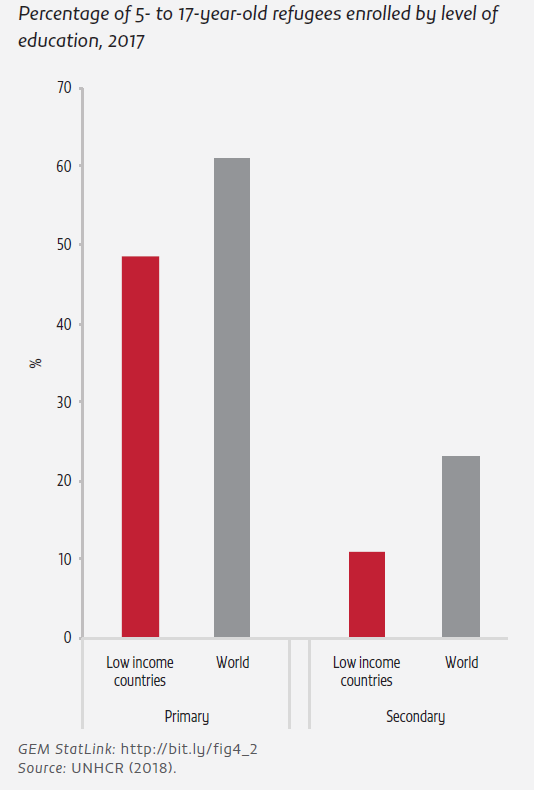

Determining the education status of the displaced is challenging, but UNHCR estimates refugee enrolment ratios at 61% in primary school and 23% in secondary school. In low income countries, the ratios were below 50% in primary and 11% in secondary (Figure 3). Overall, about 4 million refugees aged 5 to 17 were out of school in 2017.

Refugee enrolment ratios can vary considerably within countries. In 2016, the secondary gross enrolment ratio for refugees in Ethiopia ranged by district from 1% in Samara to 47% in Jijiga. In Pakistan, the 2011 primary net enrolment rate of Afghan refugees (29%) was less than half the national level (71%), while that of Afghan refugee girls (18%) was not only half that of the boys (39%), but also less than half the primary attendance rate of girls in Afghanistan. Refugees often arrive in underserved areas of host countries. Refugees in Uganda from South Sudan settle in the poor West Nile subregion, where the secondary net attendance rate was less than half the national rate in 2016.

Not much information exists on quality of refugee education, but where data are available, the picture is bleak. In the Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya, 8% of primary school teachers were certified national teachers, and 6 out of 10 refugee teachers were untrained.

Figure 3: Only 11% of refugee adolescents in low income countries are enrolled in secondary school

TRACKING EDUCATION TRAJECTORIES OF THE INTERNALLY DISPLACED IS DIFFICULT

In many conflict-affected countries, internal displacement has strained already struggling education systems. In north-eastern Nigeria, the latest education needs assessment found that out of 260 school sites, 28% had been damaged by bullets, shells or shrapnel, 20% had been deliberately set on fire, 32% had been looted and 29% were in close proximity to armed groups or military.

UNHCR reported 1.8 million people were internally displaced in Ukraine as of January 2018. In Dnipro, Kharkiv, Kiev and Zaporizhzhia, which host the most IDPs, education institutions face shortages of classroom space and resources. In response, the government has created additional school places, moved state universities from conflict regions, simplified admission procedures, covered tuition and provided incentives, including loans and textbooks, for IDPs.

Natural disasters also disrupt education, especially in Asia and the Pacific. The Philippines averages 20 typhoons a year and is at high risk for volcanic eruptions, earthquakes and landslides. The country has taken disaster risk reduction measures, and the availability of typhoon-resistant schools equipped with instructional resources has led to an average increase of 0.3 years of education.

Refugees need to be included in national education systems

Faced with crises, most governments’ reflexive response is to offer education to refugee populations in a parallel system. However, a consensus has developed that this is not a sustainable solution. Displacement is often protracted. Parallel systems usually lack qualified teachers. Examinations are not certifiable. Funding sources risk being cut off at short notice.

The 2012–2016 UNHCR global education strategy urged countries for the first time to offer refugee children access to accredited and certified learning opportunities to enable continuity in their education. The objective is to fully include refugees in the national education system so they study in the same classroom with host country children after a short period of catch-up classes, if necessary, to prepare them to enter school at the appropriate age-for-grade levels. But the degree of refugee inclusion varies across displacement contexts. Geography, history, resource availability and system capacity affect the evolving nature of inclusion.

In some cases, the move towards inclusion has been gradual. Turkey, which hosts 3.5 million refugees, first accredited non-public schools as temporary education centres, then classified them as transitional schools, and by 2020 will include all Syrian children in public schools. In other cases, government commitment has been intermittent. In the Islamic Republic of Iran, a policy of inclusion of Afghan refugees has experienced occasional setbacks over four decades.

In several cases, inclusion is not fully achieved despite a commitment to it. Refugees may share the host country’s curriculum, assessment and language of instruction but be only partially included due to geographical separation, as in camps in Kenya, or capacity constraints, as in double-shift schools in Lebanon and Jordan. Even countries with more resources, such as Greece, have faced challenges in delivering education to refugees through the national system.

In several contexts, refugee education is still provided separately. The Palestinian education system is a unique case. Burundian refugees in the United Republic of Tanzania and Karen refugees from Myanmar in Thailand attend separate, non-formal community-based or private schools.

The degree of refugee inclusion varies across displacement contexts, affected by geography, history, resource availability and system capacity

SEVERAL OBSTACLES TO INCLUSION NEED TO BE OVERCOME

Difficulties related to inclusion of refugees in national education systems are most acutely felt in contexts where capacity is weak and the need for coordination and planning is high. Plans need to recognize issues ranging from lack of documents to limited language proficiency, and from interruptions of education trajectories to poverty.

The UNESCO International Institute for Educational Planning has developed guidance on transitional education plans that focus on immediate needs and incorporate refugees and IDPs. Chad was the first country to develop such a plan in 2013. In 2018, the government converted 108 schools in 19 camps and refugee sites into regular public schools.

Refugees frequently lack documentation, which makes access to national education systems difficult. In Jordan, refugees needed a ‘service card’ to go to school, and obtaining one required a birth certificate. However, in late 2016, Jordan began allowing public schools to enrol children without service cards.

Lack of knowledge of the local language is another barrier. Burundian refugees in Rwanda enter a comprehensive orientation course lasting up to six months and join public schools when they reach the right level of English. Preparatory classes, as offered in Germany, can help, but their prolonged duration can push refugees out of the education system. Refugees’ language needs concern not just verbal communication but also non-verbal practices they can learn only if they interact with host communities.

Different kinds of programmes – bridging, remedial, catch-up and accelerated education – are needed to help displaced children access or re-enter the education system. The Norwegian Refugee Council’s accelerated learning programme in Dadaab condenses Kenya’s eight-year curriculum into four years, with multiple entry and exit points. It has increased boys’ access, though less so for girls. Ideally, such programmes should be provided by governments and incorporated into education sector plans.

Even where education is free of fees, costs such as textbooks and transport can be high. A pilot project in Lebanon, which offered cash to cover transport and compensate income forgone when children attended school instead of working, increased attendance by 0.5 to 0.7 days per week or about 20%. Turkey’s government has extended conditional cash transfers to refugees and had reached 368,000 Syrian children by 2018.

A lack of required documents, language barriers, missed education and hidden costs can hinder full inclusion

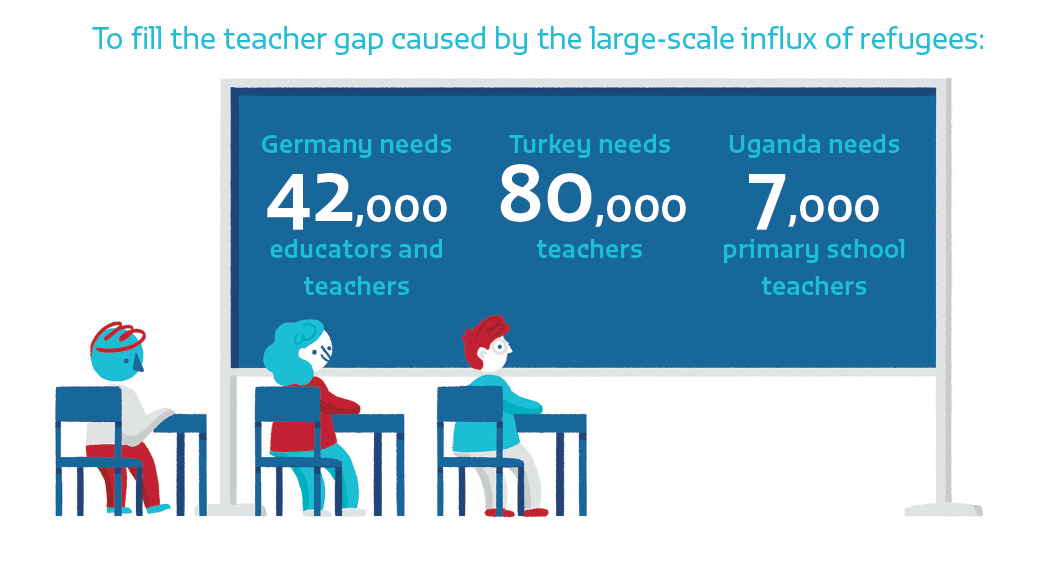

TEACHERS ARE THE KEY TO SUCCESSFUL INCLUSION

Teacher shortages, especially of qualified teachers, exist across displacement settings. Enrolment of all Syrian students in Turkey would require about 80,000 more teachers. In Germany, an additional 18,000 educators and 24,000 teachers are needed. Uganda requires 7,000 extra primary school teachers for refugee education.

Equitable and predictable teacher compensation underpins sufficient teacher supply, recruitment, retention and motivation. Yet governments and humanitarian partners, with stretched budgets and short-term funding cycles, may have trouble meeting salary costs. Using volunteer teachers, often refugees, and paying them stipends is common but disparity in teacher pay can cause tension.

Teachers in displacement contexts require training to deal with overcrowded, mixed-age or multilingual classrooms, but they often receive only sporadic support. In Lebanon, 55% of teachers and staff had participated in professional development in the previous two years, even though the presence of refugee children affected their daily teaching. Approaches used to support teachers in Kakuma camp, Kenya, range from formal teaching diploma and certificate programmes offered by a national university to a non-formal, as yet uncertified course for primary school teachers in crisis developed by the Inter-Agency Network for Education in Emergencies.

Refugee teachers are often excluded from national training programmes because of professional regulations on right to work. Some countries support refugee teachers in returning to work. Chad has trained and certified Sudanese teachers to work in its schools. In Germany, the University of Potsdam’s Refugee Teacher Programme aims to enable Syrian and other refugee teachers to return to the classroom.

Post-traumatic stress disorder prevalence rates among students have ranged from 10% to 25% in high income countries and reached as high as 75% in low and middle income countries. Where access to mental health services for children is lacking, school may be the only place such help is available. However, school-based interventions require specially trained therapists and are beyond the skills of teachers. Teachers can instead provide psychosocial support by creating a safe and supportive environment through interactions with learners and structured psychosocial activities. They need professional development on classroom management and referral mechanisms.

REFUGEES NEED EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION

Appropriate interventions, including early childhood education and care (ECEC), are crucial for young children in violent contexts who otherwise lack stable, nurturing and enriching environments. In many displacement settings, however, early learning needs go unmet.

A study of eight upper middle and high income countries suggests that responses to the needs of the youngest refugees and asylum-seekers have been ‘extraordinarily weak’, reflecting lack of priority in national policy-making and diffused responsibility for planning and delivery. A review of 26 Humanitarian and Refugee Response Plans shows that nearly half make no mention of learning or education for children under age 5, and less than one-third specifically mention pre-primary education or ECEC.

NGOs often fill the gap. The International Rescue Committee piloted the Healing Classrooms pre-school teacher education programme for Congolese children in camps in Burundi and the United Republic of Tanzania. The programme was adapted for Lebanon in 2014, where it now serves 3,200 pre-school children and has trained 128 teachers. After the four-month pilot, participants age 3 showed improved motor skills, social-emotional skills, executive function and early literacy and numeracy.

Some countries have established partnerships with multiple local and NGO actors. Ethiopia’s government supports three out of five refugee children aged 3 to 6 in 80 Early Childhood Care and Education centres in camps and 150 private and public kindergartens in Addis Ababa. The German government has adopted a comprehensive plan for refugee and asylum-seeker education, partnering with subnational actors, and plans to invest nearly EUR 400 million in 2017–2020 to expand its ECEC programmes and staff.

THE EDUCATION OF REFUGEES WITH DISABILITIES IS AT PARTICULAR RISK

International legal instruments ensure the education rights of refugee children with disabilities, but appropriate provision is rarely available. Disabilities used to be assessed by visual identification, medical assessment or volunteered information, which led to vast underestimation of the nature and rate of disabilities among displaced populations. More recent mechanisms use systematic, functionality-based questions, such as those developed by the Washington Group.

Experience of disability can vary widely according to impairment and available accommodations. A study among Afghans in Pakistan found that those with difficulty seeing were most likely to attend school (52%); those with self-care difficulties were least likely (7.5%).

Low physical accessibility – in terms of both distance and facilities – and lack of teacher training are major barriers for refugee children with disabilities, as found in Indonesia and Malaysia. There are few if any specialized schools in displacement locations, and they typically charge fees. Disabilities may also be hidden or under-reported for fear of social stigma or rejection by immigration or government authorities. Such challenges can be addressed, however. New refugee camps increasingly include accessible infrastructure, as in Jordan.

Identifying and engaging with host and refugee communities’ existing strengths is essential. A project of the umbrella organization National Union of Disabled Persons of Uganda aims to include refugees with disabilities in development activities. The Ugandan National Association of the Deaf runs schools for hearing-impaired children near two refugee settlements.

There are few if any specialized schools in displacement locations, and they typically charge fees

TECHNOLOGY CAN SUPPORT EDUCATION FOR DISPLACED PEOPLE

Forced displacement often overwhelms education systems. Technological solutions, with their scalability, speed, mobility and portability, may be well suited to help compensate for lack of standard education resources. The Instant Network Schools programme, a joint initiative of UNHCR and Vodafone, reaches more than 40,000 students and 600 teachers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya, South Sudan and the United Republic of Tanzania, providing internet, electricity and digital content.

A challenge of such interventions is that the resources provided are often not aligned with national curricula. There are some exceptions, such as Tabshoura (Chalk) in Lebanon, which offers online resources for pre-schools in line with the 2015 curriculum. Available in Arabic, English and French, it builds on Moodle, a learning management system.

Technology can also provide psychosocial support. The Ideas Box, a package developed by the NGO Libraries Without Borders and UNHCR, includes informational and cultural resources, along with education content. A qualitative evaluation in two Burundi camps hosting Congolese refugees showed a positive impact on resilience.

Most programmes support teacher professional development. In Nigeria, a UNESCO teacher education project, in association with Nokia, helped primary teachers plan lessons, ask stimulating questions, prompt reflective responses and assess students in English language and literacy classes.

Technology initiatives have their challenges. They typically require high upfront investment, and not everyone has adequate electricity and connectivity. Importantly, technology cannot substitute for participation in formal schooling. International organizations should ensure that initiatives are better coordinated and serve the ultimate aim of including refugees in national education systems.

DIVERSE TERTIARY EDUCATION INITIATIVES CATER TO REFUGEES

Tertiary education opportunities increase refugees’ employment prospects and contribute to primary and secondary enrolment and retention. Yet refugee tertiary participation is estimated at just 1%. Access is frequently neglected in emergency situations and receives coordinated attention only in cases of protracted displacement. Refugees’ tertiary education rights are often interpreted as extending to non-discrimination at most.

Technology-based initiatives can reach displaced populations. The Connected Learning in Crisis Consortium, launched by UNHCR and the University of Geneva, combines face-toface and online learning and has reached 6,500 students since 2010.

International scholarship programmes for refugees include the Albert Einstein German Academic Refugee Initiative Fund (DAFI), which has offered support to refugees through UNHCR since 1992. Geographical coverage is adjusted based on refugee movements and education needs. Currently, the largest programmes are in Turkey, Ethiopia, the Islamic Republic of Iran and Lebanon.

Other scholarship programmes offer opportunities to study in high income countries. The Student Refugee Program of the World University Service of Canada supports university-based committees wishing to sponsor a refugee for resettlement and study at their institution. Since 1978, it has brought over 1,800 refugees from 39 countries to over 80 colleges and universities across Canada.

Academics may also need support. Scholars at Risk arranges temporary research and teaching positions for academics needing protection. The Council for At-Risk Academics (CARA) in the United Kingdom provides urgent support, particularly to academics in immediate danger in home countries.

The benefits of support should extend to the wider community. DAFI scholarships recognize origin communities as intended beneficiaries, beyond the scholarship recipient. Networks to support refugee academics can also promote capacity-building. CARA has launched programmes to rebuild research and teaching capacity in Iraq, the Syrian Arab Republic and Zimbabwe.

Only 1% of refugees are in tertiary education

IDPs tend to face education challenges similar to those of refugees

Although the UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement state that everyone has the right to education, capacity and politics hamper both recognition of the problem and coordination over solutions. The legal, educational and administrative responses to the education plight of the internally displaced are often similar to those described for refugees.

The government of Colombia, where 6.5 million IDPs live as of 2017, has focused on the legal protection framework. In 2002, the Constitutional Court instructed municipal education authorities to treat displaced children preferentially in terms of access to education. In 2004, the court declared that IDPs’ fundamental rights, including the right to education, were being violated.

Displacement means many children’s and adolescents’ education trajectories are interrupted and they need support to re-enter the education system. In Afghanistan, Children in Crisis, an NGO, runs a community-based accelerated programme to help out-of-school internally displaced students living in informal settlements in and around Kabul complete grade 6 and transition into formal education.

Internally displaced teachers often remain under the administrative supervision of their home district, which makes collecting salaries virtually impossible, as in the Syrian Arab Republic. In Iraq, 44 partners provide services across 15 governorates and support around 5,200 teachers with stipends or incentives, although poor coordination has led to service gaps, pay disparity among teacher categories and tension among partners.

Internally displaced teachers often face risks and administrative hurdles that make collecting salaries virtually impossible

Natural disasters and climate change require education systems to be prepared and responsive

Education sector plans need to take into account the risks of loss of life, infrastructure damage and displacement from natural disasters and ensure that education services are as little disrupted as possible, from emergency response to recovery. In 2017, the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction and the Global Alliance for Disaster Risk Reduction and Resilience in the Education Sector launched their updated Comprehensive School Safety framework. Its three pillars are safe learning facilities, school disaster management, and risk reduction and resilience education.

Many Pacific island nations take climate change risk into account in education plans. In 2011, the Solomon Islands Policy Statement and Guidelines for Disaster Preparedness and Education in Emergency Situations aimed to ensure that students continued to have access to safe learning environments before, during and after an emergency, and that all schools identified temporary learning and teaching space.

Within a few decades, climate may be one of the main reasons for displacement. The World Bank estimates that 140 million people will be displaced due to climate change by 2050. In order to reduce vulnerability, some countries are already considering policy responses. The Kiribati government’s ‘migration with dignity’ policy, part of a long-term nationwide relocation strategy, aims to raise people’s qualifications and give them tools for access to decent work opportunities abroad in occupations such as nursing.

Previous year