Introduction: Migration, displacement & education

Powerful, moving stories of migration and displacement occur around the world. These stories of ambition, hope, fear, anticipation, ingenuity, fulfilment, sacrifice, courage, perseverance and distress remind us that ‘migration is an expression of the human aspiration for dignity, safety and a better future. It is part of the social fabric, part of our very make-up as a human family’. Yet migration and displacement are ‘also a source of divisions within and between States and societies …

Burundian refugee, Nigirabarya, 31, is head teacher at Hope Secondary School in Nduta refugee camp, Tanzania. Credit: Georgina Goodwin/UNHCR

In recent years, large movements of desperate people, including both migrants and refugees, have cast a shadow over the broader benefits of migration’.

While there is shared responsibility for the common destiny formally endorsed in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, migration and displacement continue to elicit some negative responses in modern societies. These are exploited by opportunists who see benefit in building walls, not bridges. It is here that education’s role to ‘promote understanding, tolerance and friendship among all nations, racial or religious groups’, a key commitment in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, takes centre stage.

This report looks at migration and displacement through the eyes of teachers and education administrators faced with the reality of diverse classrooms, schoolyards, communities, labour markets and societies. Education systems around the world are united in the commitment to ‘ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all’ and to ‘leave no one behind’. For all students to fulfil their promise, systems need to adjust to their needs irrespective of their backgrounds. They also need to respond to societies’ need to be resilient and adapt to migration and displacement – a challenge affecting countries with large and small migrant and refugee populations alike.

All types of population movement are covered. On average, one out of eight people is an internal migrant. This migration can have serious effects on the educational opportunities of those moving and those left behind, particularly in still rapidly urbanizing low and middle income countries. About 1 out of 30 people lives in a country other than the one where they were born. Almost two-thirds of international migrants are destined for high income countries. While most move to work, some also move for education. And international migration also affects the education of their descendants. Some 1 out of 80 people are displaced within or across borders by conflict or natural disasters. Nine out of ten of these live in low and middle income countries. Including them in national education systems is crucial but can be conditioned by the unique contexts of the displacement.

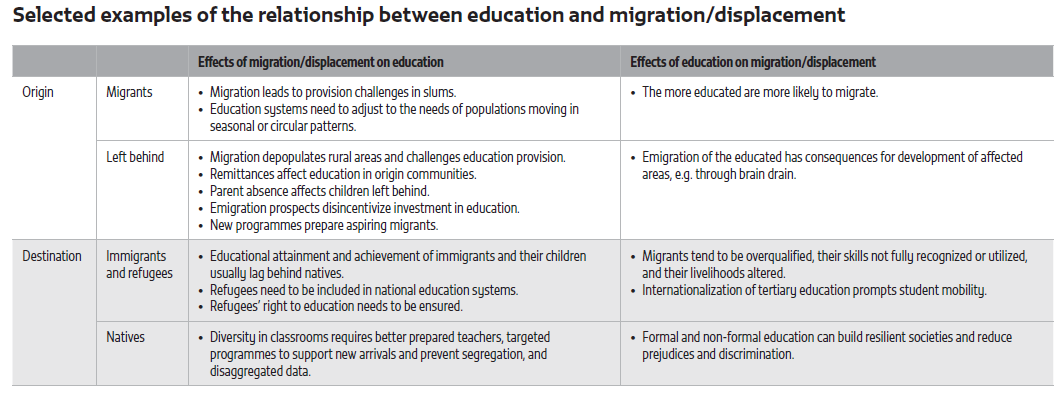

Migration and displacement interact with education through intricate, two-way relationships that affect those who move, those who stay and those who do or may host migrants and refugees (Table 1). When in the life cycle people ponder or undertake migration is a key determinant of education investment, interruption, experience and outcome. Children migrating from areas with lower levels of education development may access opportunities otherwise unavailable. At the same time, migrant students’ attainment and achievement often lag behind those of their peers in destination communities.

TABLE 1: Selected examples of the relationship between education and migration/displacement

Migration and displacement require education systems to accommodate the needs of those who move and those left behind. Countries need to recognize migrants’ and refugees’ right to education in law and fulfil this right in practice. They need to tailor education for those cramming into slums, living nomadically or awaiting refugee status. Education systems need to be inclusive and fulfil the commitment to equity. Teachers need to be prepared to deal with diversity and the traumas associated with migration and, especially, displacement. Recognition of qualifications and prior learning needs to be modernized to make the most of migrants’ and refugees’ skills, which contribute greatly to long-term prosperity.

Education also profoundly affects migration and displacement – both their volume and how they are perceived. Education is a major driver in the decision to migrate, fuelling the search for a better life. It affects migrants’ attitudes, aspirations and beliefs, and the extent to which they develop a sense of belonging in their destination. Increased diversity in classrooms has challenges, including for natives (especially the poor and marginalized), but it also offers opportunities to learn from other cultures and experiences. Curricula sensitive to addressing negative attitudes are needed more than ever.

With migration and displacement becoming hot political topics, education is key to providing citizens with a critical understanding of the issues involved. It can support the processing of information and promote cohesive societies, especially important in a globalized world. Yet education should go well beyond tolerance, which can betray indifference; it is a critical tool in fighting prejudice, stereotypes and discrimination. If poorly designed, education systems can promulgate negative, partial, exclusive or dismissive portrayals of immigrants and refugees.

The 2019 Global Education Monitoring Report reviews global evidence on migration, displacement and education and aims to answer the following questions:

- How do population movements affect access to and quality of education? What are the implications for individual migrants and refugees?

- How can education make a difference in the lives of people who move and in the communities receiving them?

Migration and displacement require education systems to accommodate the needs of those who move and those left behind

The world is moving to address the education and other needs of migrating, displaced and hosting populations Addressing the education and other needs of migrating, displaced and hosting populations at the local, national and international levels requires mobilizing resources and coordinating actions. The world is moving in that direction. In September 2016, 193 UN member states signed the New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants to strengthen and refine responsibilitysharing mechanisms, setting in motion processes for two global compacts: one on migrants and the other on refugees.

The draft Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration puts most issues addressed in this report on the agenda. It covers access to basic services, including education both in and beyond school. Although more emphasis is given to skills recognition, it conveys a generally positive message about education as an opportunity to make the most of migratory flows. However, the compact is non-binding and leaves open how countries meet commitments.

Providing education to the displaced requires additional support to help people adjust to new environments and cope with protracted displacement. Although refugees’ right to education in host countries is guaranteed in the 1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, the Global Compact on Refugees aims to renew the commitment. The final draft dedicates two paragraphs to education, focusing on finance and its use to support specific policies. It makes clear the need for the development of national policies on inclusion.

Foreword by Audrey Azoulay

People have always moved from one place to another, some seeking better opportunities, some fleeing danger. These movements can have a great impact on education systems. The 2019 edition of the Global Education Monitoring Report is the first of its kind to explore these issues in-depth across all parts of the world.

The Report is timely, as the international community finalizes two important international pacts: the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, and the Global Compact on Refugees. These unprecedented agreements – coupled with the international education commitments encapsulated in the fourth United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) – highlight the need to address education for migrants and the displaced. This GEM Report is an essential reference for policy-makers responsible for fulfilling our ambitions.

Currently, laws and policies are failing migrant and refugee children by negating their rights and ignoring their needs. Migrants, refugees and internally displaced people are some of the most vulnerable people in the world, and include those living in slums, those moving with the seasons to eke out a living and children in detention. Yet they are often outright denied entry into the schools that provide them with a safe haven and the promise of a better future.

Ignoring the education of migrants squanders a great deal of human potential. Sometimes simple paperwork, lack of data or bureaucratic and uncoordinated systems mean many people fall through administrative cracks. Yet investing in the education of the highly talented and driven migrants and refugees can boost development and economic growth not only in host countries but also countries of origin.

Provision of education in itself is not sufficient. The school environment needs to adapt to and support the specific needs of those on the move. Placing immigrants and refugees in the same schools with host populations is an important starting point to building social cohesion. However, the way and the language in which lessons are taught, as well as discrimination, can drive them away.

Well-trained teachers are vital for ensuring the inclusion of immigrant and refugee pupils but they too need support in order to manage multilingual, multicultural classes, often including students with psychosocial needs.

A well-designed curriculum that promotes diversity, that provides critical skills and that challenges prejudices is also vital, and can have a positive ripple effect beyond the classroom walls. Sometimes textbooks include outdated depictions of migrations and undermine efforts towards inclusion. Many curricula are also not flexible enough to work around the lifestyles of those perpetually on the move.

Expanding provision and ensuring inclusion require investment, which many host countries cannot meet alone. Humanitarian aid is currently not meeting children’s needs, as it is often limited and unpredictable. The new Education Cannot Wait fund is an important mechanism for reaching some of the most vulnerable.

The message of this Report is clear: Investing in the education of those on the move is the difference between laying a path to frustration and unrest, and laying a path to cohesion and peace.

Audrey Azoulay

Director-General of UNESCO

Foreword by Helen Clark

The 2019 Global Education Monitoring Report has been brought together by a team of international migrants. Four of its members are children of refugees. They don’t deny that people look at migration – and migrants – from different viewpoints. Their research demonstrates the extent to which education can help open up those perspectives and bring greater opportunities for all.

For migrants, refugees and host communities, there is the known and the unknown. All that some people know, however, is deprivation and the need to escape from it; they don’t know whether there will be opportunity at the other end. In recipient communities, people may not know whether and how their new neighbours, wearing different clothes, having different customs, and speaking with a different accent, will change their lives.

Migration is characterized by both order and disorder. Societies often strive to manage population movements but nonetheless may face unpredictable inflows. Such movements may create new divisions, while others have demonstrably benefited both source and destination countries.

In migration flows, we see both will and coercion. Some people move proactively to work and study while others are forced to flee persecution and threats to their livelihoods. Recipient communities and politicians may argue interminably whether those who arrive are pushed or pushing, legal or illegal, a boon or a threat, or an asset or a burden.

There is both welcoming and rejection. Some people adjust to their new environment while others cannot. There are those who want to help and those who want to exclude.

Thus, around the world, we see migration and displacement stirring great passions. Yet there are decisions to make. Migration requires responses. We can raise barriers, or we can reach out to the other side – to build trust, to include, to reassure.

At the global level, the United Nations has worked to bring nations together around durable solutions to migration and displacement challenges. During the UN Summit on Refugees and Migrants in 2016, I called for investing in conflict prevention, mediation, good governance, the rule of law and inclusive economic growth. I also drew attention to the need for expanding access to basic services to migrants to tackle inequalities.

This Report takes that last point further by reminding us that providing education is not only a moral obligation of those in charge of it, but also is a practical solution to many of the ripples caused by moving populations. It must be, and should always have been, a key part of the response to migration and displacement – an idea whose time has come, as the texts of the two global compacts for migrants and refugees show.

For those denied education, marginalization and frustration may be the result. When taught wrongly, education may distort history and lead to misunderstanding.

But, as the Report shows us in the form of so many uplifting examples from Canada, Chad, Colombia, Ireland, Lebanon, the Philippines, Turkey and Uganda, education can also be a bridge. It can bring out the best in people, and lead to stereotypes, prejudices and discrimination being discarded for critical thinking, solidarity and openness. It can offer a helping hand to those who have suffered and a springboard to those who desperately need opportunity.

This Report points directly to a major challenge: How can teachers be supported to practise inclusion? It offers us fascinating insights into humanity and the age-old phenomenon of migration. I invite you to consider its recommendations and to act on them.

The Right Honourable Helen Clark

Chair of the GEM Report Advisory Board

Previous year